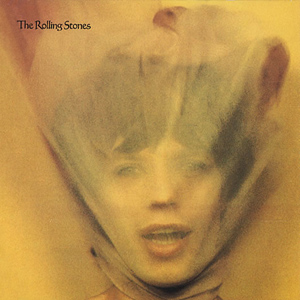

Goats Head Soup seems like a hangover, the dark side of the decadence so celebrated on the last couple of Stones albums. There’s an evil undercurrent here, and it doesn’t make for easy listening. Perhaps it’s the shrouded cover art; perhaps it’s the insistence that the album was recorded in Jamaica but there’s hardly any influence to be detected. That incongruousness is no more blatant than in “Winter”, which conjures mental images of snow, Christmas trees and harsh winds—hardly the stuff of a week spent recording in Kingston.

Goats Head Soup seems like a hangover, the dark side of the decadence so celebrated on the last couple of Stones albums. There’s an evil undercurrent here, and it doesn’t make for easy listening. Perhaps it’s the shrouded cover art; perhaps it’s the insistence that the album was recorded in Jamaica but there’s hardly any influence to be detected. That incongruousness is no more blatant than in “Winter”, which conjures mental images of snow, Christmas trees and harsh winds—hardly the stuff of a week spent recording in Kingston.The darkness is apparent from the start, as “Dancing With Mr. D” takes place in a graveyard. “100 Years Ago” is a little schizophrenic, starting with a funky clavinet and changing gears halfway through with a slower section before delving back into the darkness. The tender “Coming Down Again” is a showcase for Keith and Nicky Hopkins, a lament over either infidelity, drug abuse or both. “Doo Doo Doo Doo Doo (Heartbreaker)” turns it back up, bringing in the funk, heavy on the keyboards and full of anger. Not content to let Keith tug the heartstrings all by himself, Mick delivers “Angie”, all tenderness and strings, with a whispered section that gets creepier every year.

“Silver Train” brings back the boogie, but “Hide Your Love” sounds like it was recorded on the spot. “Winter” takes over the center of the album, just as “Coming Down Again” did on side one; it transcends its few chords and perfectly captures an ache better than “Angie”. Even the strings work. “Can You Hear The Music?” was probably the only way to follow this, with its finger cymbals and faux-mystical lyrics. And just to prove they could still push buttons, “Star Star” relies on a certain four-letter word repeated about 97 times over a standard Chuck Berry riff to cause controversy.

Ultimately, Goats Head Soup is something of a disappointment, since it had to follow the stellar track record of all the amazing albums that have gone before. It’s still good, and highly recommended, but we can start to see the laziness that would be the brand’s trademark going forward.

With their usual strange idea of when albums should be upgraded, the 47th birthday of Goats Head Soup was commemorated with a new stereo mix by Giles Martin, seemingly on a break from all his work on Beatles box sets. A disc of “rarities and alternate mixes” in the Deluxe Edition delivered exactly that, including instrumental runthroughs and negligible alternates of “Dancing With Mr. D” and “Heartbreaker”, alternates of “Silver Train” and “Hide Your Love”, and a demo of “100 Years Ago”. Two of the best outtakes had long been part of Tattoo You, so only three unreleased songs are added to the program. Naturally “Scarlet”, featuring Jimmy Page on lead guitar, is of wide interest, but it was recorded by only Mick and Keith with Ric Grech on bass and another drummer in late 1974, nearly two years after the original Goats Head Soup album sessions, and over a year after the album had been released. “All The Rage” is a decent rocker with obviously brand-new vocals, and while Mick says he didn’t touch “Criss Cross”, it appears to have new percussion from Jim Keltner. (The pricey Super Deluxe Edition also offered, among artwork and a thick book, another CD containing Brussels Affair, the official bootleg of a 1973 concert previously only available via download or in an even more expensive box set.)

The Rolling Stones Goats Head Soup (1973)—3½

2020 Deluxe Edition: same as 1973, plus 10 extra tracks (Super Deluxe Edition adds another 15 tracks plus Blu-ray)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-15331898-1589859839-1394.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-1104728-1192364101.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-68430-1544367763-7328.jpeg.jpg)

.jpg)