Back in 1991, Guns N’ Roses had been taking an eternity to complete their next album. They were touring to promote it while still tinkering with it, to the extent that

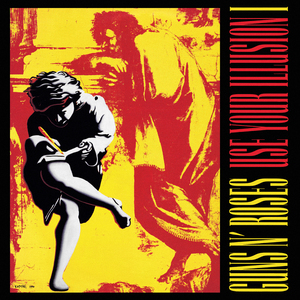

Use Your Illusion would finally arrive as two double-album-length CDs, available separately. This was the biggest thing to happen in the record business in years, as demonstrated by nationwide midnight sales. Nobody wanted to be the only one at school to not have the new GN’R albums, and everyone had to have them both.

Use Your Illusion I, or the red and yellow one, was probably the closest in spirit to the debut, in that it was more about straight-ahead rock. By now Steven Adler had been bounced from the band, replaced by Matt Sorum, who was best known for touring with the Cult, but had also done time with a woman soon to be known as Tori Amos. He was, and is, a heavy hitter, exactly the type of drummer needed to fill a stadium P.A., but frankly lacked the swing that Adler exhibited on the first album. Another sign that we’re on the other side of the bell curve is the individual writing credits; where previous songs were credited to the band as a whole, now it was clear which ones Axl Rose wrote by himself, and moreso when it was an Izzy Stradlin tune.

Duff McKagan’s bass and a Slash riff kick off “Right Next Door To Hell”, one of several rapid-fire vocals from Axl. Izzy takes the first of three(!) lead vocals on the album for “Dust N’ Bones”, though it’s mostly buried under Slash’s lead line. Their cover of Wings’ “Live And Let Die” was surprising yet nearly note-for-note, but most people were probably on board for “Don’t Cry”, their new power ballad and smash single, and wondering if he really held that last note for 30 seconds. “Perfect Crime” is more high-speed yelling, and best during the slower break.

Izzy dominates what LP owners called side two, starting with “You Ain’t The First”, which could have fit on side two of Lies. Michael Monroe of Hanoi Rocks honks harmonica and saxophone on “Bad Obsession”, and we can also hear new member Dizzy Reed on piano. It’s one of several songs here that garnered the parental advisory sticker and prevented the album(s) from being sold at stores like Walmart, along with the overly angry “Back Off Bitch”. “Double Talkin’ Jive” is another piledriver riff, mostly sung by Izzy with Axl helping, that manages to find its way to an extended flamenco-style coda.

The centerpiece of the album was “November Rain”, the epic piano-based showstopper Axl had been concocting since he bought his first Elton John album. It was made even more inescapable in those days thanks to its over-the-top video, which ran the full length of the song’s nine minutes. (The canned strings used on the original album were replaced thirty years later by actual strings for the album’s Deluxe Edition, and still sound cheesy.) “The Garden” begins somewhat subdued, and wanders around one chord until Alice Cooper’s guest appearances. It tends to drag, which can’t be said about the oddly sequenced “Garden Of Eden”, which is twice the speed and half the length. “Don’t Damn Me” is this volume’s response to Axl’s critics over his homophobia, racism, misogyny, etc. It’s another song that benefits from the dynamics of a slowed-down midsection.

“Bad Apples” begins with a taste of funk but soon descends into straight boogie, while “Dead Horse” is bookended by Axl singing and strumming his acoustic, in the same style as the main, heavier meat of the song. All this is a mere prelude to “Coma”, which Axl and Slash wrote after separate overdoses and takes up the final ten minutes of the album. The riff offsets the heartbeat kick drum, and spoken interludes by medical experts with matching sound effects aren’t too gratuitous—though the nagging female voices don’t evoke much sympathy for the singer’s plight—and the cyclical music manages to support Axl’s closing rant.

As with most double albums, Use Your Illusion I could have easily been shaved down to a single, but that wasn’t part of the plan. Considering that two of the best songs together took 20 minutes, Izzy likely would have seen only one of his songs included, if at all, had they tried to condense it. But we can only take so much of Axl’s wordy screaming song after song—even he needed a teleprompter onstage to get all the words right.

In addition to the new mix of “November Rain” inserted into to the original sequence, the album’s Deluxe Edition added an hour’s worth of live tracks from a variety of shows—mostly songs from the album, plus such unique tunes as a cover of the Misfits’ “Attitude” sung by Duff, “Always On The Run” with Lenny Kravitz (who wrote the song with Slash), “November Rain” prefaced by Black Sabbath’s “It’s Alright”, and a mostly instrumental take on the Stones’ “Wild Horses”. Shannon Hoon, eventually of Blind Melon, sings on two songs. Not all of these were included in the seven-CD-plus-Blu-ray Super Deluxe Edition, which added two full concerts: two discs from the Ritz (the former Studio 54) at the start of the tour, and three discs from Las Vegas eight months into it. A lot of music, to be sure.

Guns N’ Roses Use Your Illusion I (1991)—3

2022 Deluxe Edition: “same” as 1991, plus 13 extra tracks

Like a lot of bands, Fairport Convention truly hit their stride with their third album. On Unhalfbricking they moved much closer to electrified English folk, setting the standard for others to follow. By this time Ian Matthews had left the band, bringing the core members down to five, but the presence of Dave Swarbrick on fiddle and mandolin would lead to his joining full-time, and we’re getting ahead of ourselves again.

Like a lot of bands, Fairport Convention truly hit their stride with their third album. On Unhalfbricking they moved much closer to electrified English folk, setting the standard for others to follow. By this time Ian Matthews had left the band, bringing the core members down to five, but the presence of Dave Swarbrick on fiddle and mandolin would lead to his joining full-time, and we’re getting ahead of ourselves again.