That’s not to say they’d gone soft in the slightest. If you’re looking for power and commentary, the title track kicks it off for you, a virtual siren of doom. The first cover of several on the album is “Brand New Cadillac”, a rockabilly favorite that’s another great showcase for Joe Strummer’s voice. (C’mon, how can you beat “Baby baby drove up in a Cadillac/I said ‘Jesus Christ, where’d you get that Cadillac?”) Things turn down for “Jimmy Jazz”, which isn’t jazz save a couple chords and a sax solo, but it’s the first time we learned how the Brits pronounce the last letter of the alphabet. “Hateful” speeds up the Bo Diddley beat and adds a catchy melody, and given the reliance on covers, “Rudie Can’t Fail” is especially surprising for its authentic ska arrangement. Plus, we like Joe’s exhortation to Mick Jones: “Sing, Michael, sing!”

“Spanish Bombs” is one of the catchier tunes about the Spanish Civil War, nicely layered with subtle acoustic guitars, organ, and octave harmonies. A personal favorite is “The Right Profile”, a horn-driven portrait of beleaguered actor Montgomery Clift, with one of the greatest lyrics of all time, which we’ve transcribed directly from the sleeve: “Arrrghhhgorra buh bhuh do arrrrgggghhhhnnnn!!!!...” While Joe wrote it, he must have known Mick was the best conduit for “Lost In The Supermarket”, so simple and somehow fragile. That feeling is wiped aside by the more urgent “Clampdown”, with an organ part we think is courtesy of Mickey Gallagher from Ian Dury’s Blockheads. For a real departure, Paul Simonon sings his own dark and brooding composition, “The Guns Of Brixton”. His voice is all but tuneless, but it works.

To keep everyone guessing, “Wrong ‘Em Boyo” begins as a cover of the ancient “Stagger Lee” before switching tempo and key and everything to the reggae tune of the actual title. “Death Or Glory” gets an awful lot of action out of its three chords, weaving well in and out of choruses and verses, showing their grasp of dynamics. (This would be a good place to praise drummer Topper Headon, who handles every tempo and style they throw at him.) Though it goes by too fast to understand most of the words, “Koka Kola” carefully avoids copyright infringement while putting a new spin on the phrase “coke adds life”. The only song on the album credited as written by the whole band, “The Card Cheat” pulls in Phil Spector’s magnificent Wall of Sound and mariachi horns for another tale of an outlaw’s demise.

Despite the misplaced apostrophe, “Lover’s Rock” is poppy and fun, with lots of wacky percussion things poking in and out of the mix. Another one that needs the lyric sheet to decipher, “Four Horsemen” presents the band themselves as the mythical figures of the title, and is poignant today given their limited time together. “I’m Not Down” is more wonderfully hook-laden pop, whereas “Revolution Rock” is another reverent reggae cover that would prove highly influential to Californian white kids generation later.

Possibly the album’s most famous song isn’t listed on the cover, label, or lyric sheet. More to the point, “Train In Vain” is the tune everyone thinks of as “Stand By Me” and was originally hidden at the end of Side 4. It was added so late in the process that some of the stickers only counted 18 tracks and not 19, but if you looked carefully at the runout groove on that side, you could see “TRACK 5 IS TRAIN IN VAIN” etched there. Even later cassettes and CDs didn’t mention it.

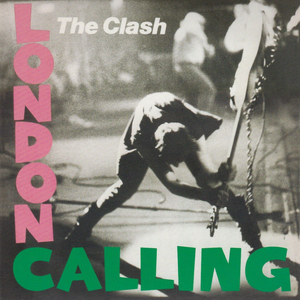

Released on the cusp of a new decade, London Calling firmly established the band as important, and turned the punk scene on its ear. Perhaps it could have been shaved from two LPs to one, but what would you leave out? If you’re going to have just one Clash album, this would probably be the one to choose; besides being solid start to finish, it was priced well, at least until the digital era. So after much ruminating, we’ve awarded it the rating below.

The album was nicely upgraded for its silver anniversary, with not only a DVD and liner notes but a bonus disc full of pre-album rehearsals, including several songs (and covers) that would make the album proper, plus a surprising take on a reggae cover of Bob Dylan’s relatively obscure “The Man In Me”. (Later reissues replicated the album on two CDs, despite previously fitting on one.)

The Clash London Calling (1979)—5

2004 25th Anniversary Legacy Edition: same as 1979, plus 21 extra tracks (and DVD)