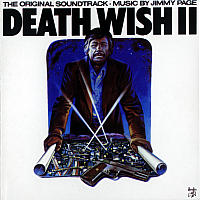

After Led Zeppelin announced their breakup following the death of John Bonham, everything was quiet except the rumor mill. Amazingly the first of the survivors to surface was Jimmy Page, and in an unlikely fashion.

Death Wish II was the unexpected (after eight years) sequel to the notorious original thriller starring Charles Bronson as beleaguered architect Paul Kersey. Now it was the ‘80s, his loved ones were still getting raped and murdered, and only he could avenge them. And this time, his theme music would be provided by Jimmy, with the soundtrack on Swan Song Records. Jimmy’s last attempt to score a film—Kenneth Anger’s Lucifer Rising—didn’t get too far, so he at least made the effort to buckle down this time.

“Who’s To Blame”, the opening track and main theme from the opening credits, sports a stomp and feel akin to “In The Evening” from In Through The Out Door, so that’s not too unexpected. Dave Mattacks, most famous from Fairport Convention, ably pounds the kit with Bonham-like power, but rather than Robert Plant’s familiar wail, we get Chris Farlowe, who has an extremely blustery, distracting voice. Being a soundtrack, vocals take a back seat to instrumental atmospheres, such as what we hear on “The Chase”. The credits on the inner sleeve are very helpful in noting who’s playing on what part of which track, particularly when it’s one of Jimmy’s synthesizers. Suspense is heightened and sustained, accordingly. “City Sirens” is sung weedily by Gordon Edwards, who played in the Swan Song incarnation of the Pretty Things, and is little more than a two-minute sketch of a song that might have been developed further in a band setting. And because it’s a soundtrack, tracks get titles like “Jam Sandwich”, which is little more than a riff. “Carole’s Theme” is pretty in its sadness, pretty when he plays the theme himself on acoustic. Another orchestral flourish leads to “The Release”, a decent theme for the closing credits, strangely ending side one.

Much of what’s left is further atmosphere. “Hotel Rats And Photostats” combines two sections, including what sounds like a fretless bass in a harbinger of things to come. More interesting is “Shadow In The City”, full of harmonics, bowed guitars, and Theremin, refugees from the unfinished Lucifer Rising soundtrack. “Jill’s Theme” seemingly refers to the actress and not a character, and it’s a double shame that her theme is another tense orchestral demonstration. In contrast, “Prelude” (adapted from a Chopin piece but not credited that way) is a perfect showcase for Jimmy’s style, playing the teary melody over sympathetic keys and rhythm section. But then there’s “Big Band, Sax, And Violence”, which uses canned brass to represent the sound of the title. Finally, there’s a fairly generic rocker in the form of “Hypnotizing Ways (Oh Mamma)”, Farlowe’s vocals mixed thankfully low.

Being all we heard from Jimmy Page in those wilderness years, the Death Wish II soundtrack wasn’t immediately encouraging. Anyone who paid to see the film because of the connection would have been confronted by graphic violence and gang rapes, and subsequent playings of the album only bring back those images. Still, it has it moments, specifically the Chopin prelude and one or two of the instrumentals, but it’s still not much easier to recommend than the actual film. It was, after all, designed as background music.

The album has been long out of print since its original release, with only Japan approving a CD in the late ‘90s. Jimmy himself distributed a pricey vinyl-only version via his website in 2011, deleting “Big Band, Sax, And Violence” and adding “Main Theme” (basically, “Who’s To Blame” without vocals) at the end. Four years later, the same sequence was included in a hefty box called Sound Tracks, which included another half hour of cues and ideas—including a demo from the mid-‘70s—as well as two discs (totalling one hour) dedicated to Lucifer Rising. All in all, spooky stuff.

Jimmy Page Death Wish II: The Original Soundtrack (1982)—2

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-1894838-1414013024-2401.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-4748668-1374266705-2586.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-1814034-1300384076.jpeg.jpg)