The title of

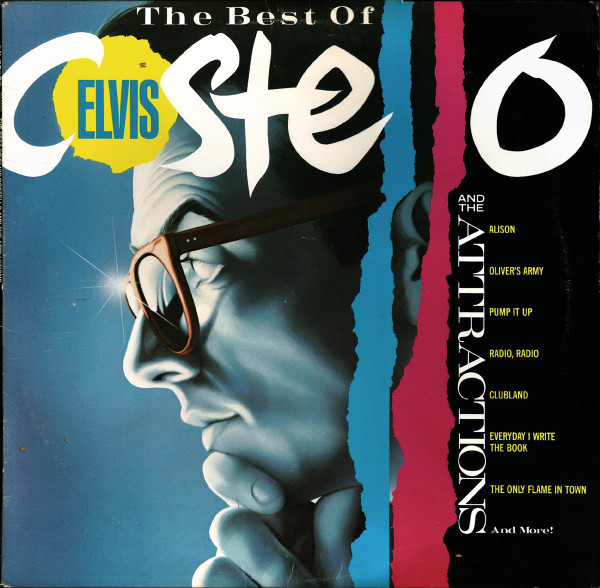

his previous album—along with the lyrical tone and subsequent critical reaction—hinted strongly that some kind of transitional period was necessary, and with no new Elvis Costello album in 1985, both the US and the

UK were treated to compilations in time for Christmas. Besides having better cover art, the American release pointedly credited the Attractions on the front, spine, and label, and sported a mostly chronological sequence of songs. (The CD version even added three extra tracks, all excellent choices.) Though it would go out of print once the catalog was reissued and replaced by other attempts to sum him up in a disc or two, this was a terrific doorway into the catalog, and primed the pump for the next real album, which appeared only months later.

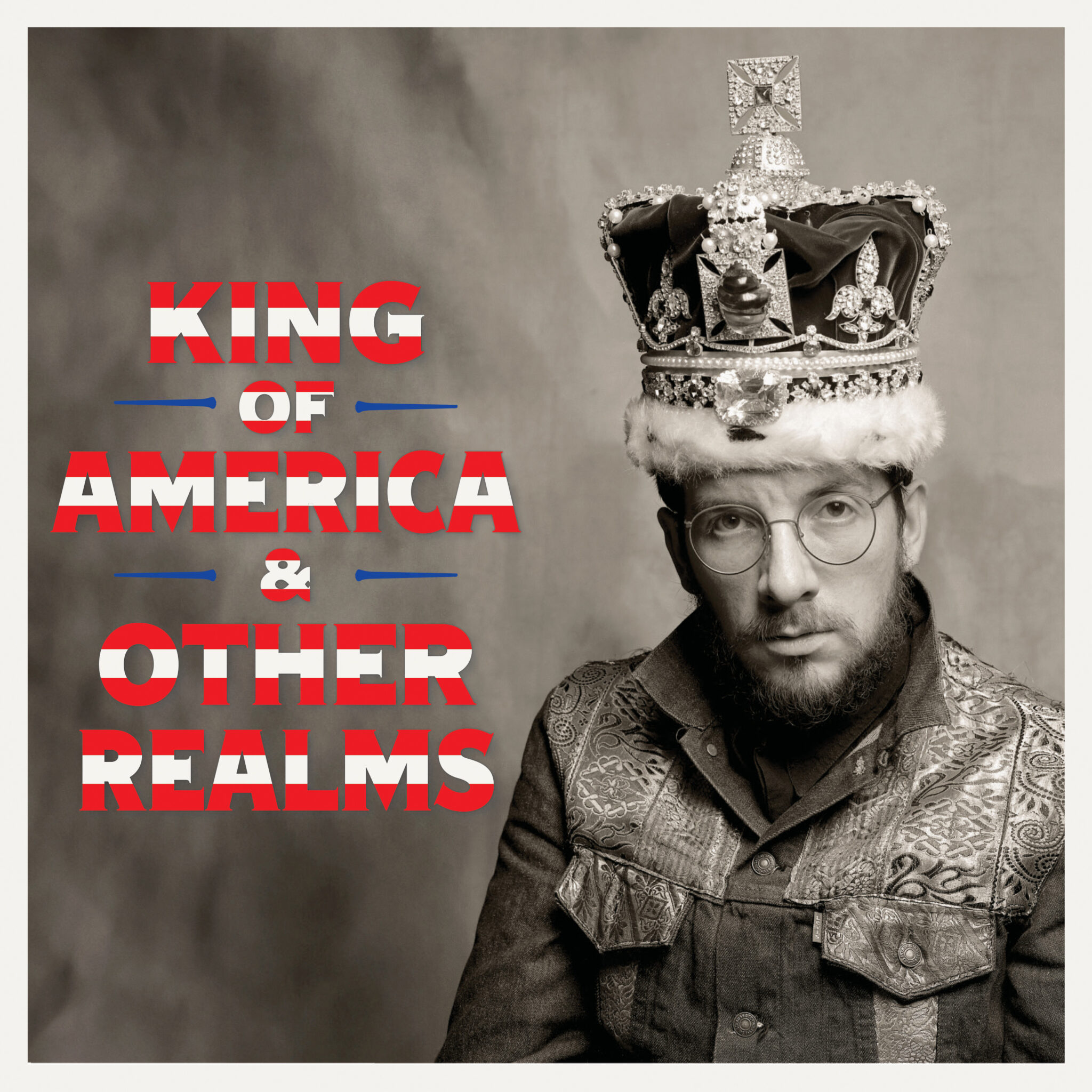

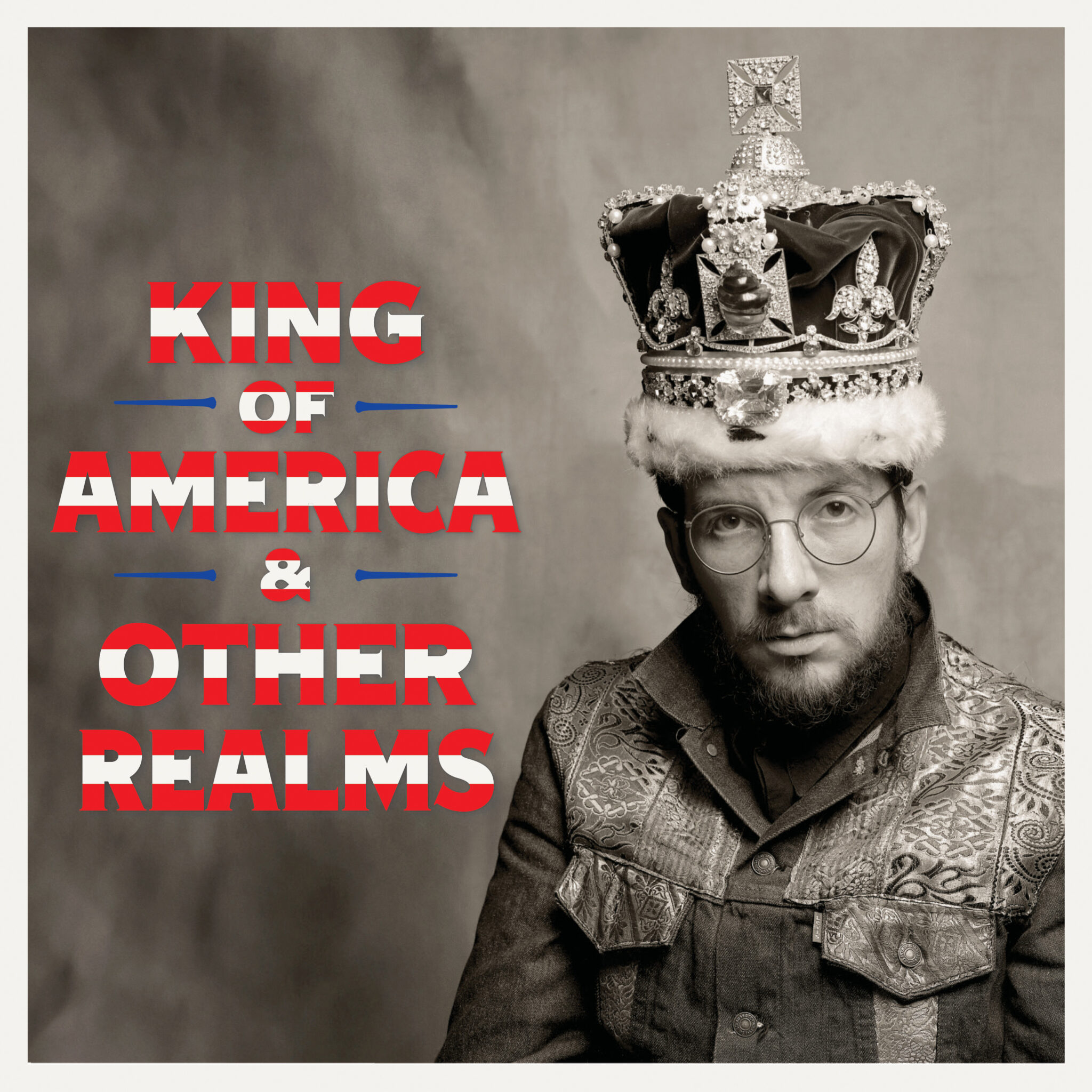

As if to confirm the implicit threat of Goodbye Cruel World, Elvis had embarked on a series of sessions produced by new buddy T Bone Burnett, with a rotating cast of American session guys, collectively dubbed The Confederates. He’d already reverted to using his given name of Declan MacManus to copyright his songs, but management insisted he stick with the established brand for the time being, so King Of America was credited to The Costello Show (to which Columbia in the US made sure to add “featuring Elvis Costello” in parentheses on the spine and labels in case nobody recognized the face behind the beard on the cover).

As if to confirm the implicit threat of Goodbye Cruel World, Elvis had embarked on a series of sessions produced by new buddy T Bone Burnett, with a rotating cast of American session guys, collectively dubbed The Confederates. He’d already reverted to using his given name of Declan MacManus to copyright his songs, but management insisted he stick with the established brand for the time being, so King Of America was credited to The Costello Show (to which Columbia in the US made sure to add “featuring Elvis Costello” in parentheses on the spine and labels in case nobody recognized the face behind the beard on the cover).

From the start, the sound is much different to both the current music scene as well as Elvis’s own trajectory, making for a startling but ultimately rewarding listen. Acoustic guitars, mandolins, and string basses drive the songs, with pianos, organs, and accordions providing the extent of the keyboards. Nearly all the songs are upbeat, and even the slow ones don’t drag.

Opening with “Brilliant Mistake”, which provides the album’s title, the album kicks off at a steady trot that continually satisfies. (After the Bruce Springsteen song of a similar title became better known, Elvis would occasionally modify the third verse to reference it; he’s also been known to work in a quote of Bob Dylan’s “Tangled Up In Blue” due to the chordal similarity.) “Lovable” is a singalong with David Hidalgo of Los Lobos and a very successful use of key changes. The sentimental portrait of “Our Little Angel” is just one of several saloon-based songs here. If there’s a clunker here, it would be the cover of the Animals’ “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood” (though he would probably insist he heard Nina Simone’s first), delivered at a seething pace yet still released as a single. But it still works, and leads well into “Glitter Gulch”, which derides Vegas and game shows. “Indoor Fireworks” is a sad lament working every possible metaphor and “Little Palaces” is a bitter indictment of the Thatcher regime, tempered by “I’ll Wear It Proudly” is one of his most tender love songs.

In between the accordions, “American Without Tears” relates an encounter in a different kind of saloon, and its view of history is underscored by the drunken protest in the obscure cover of J.B. Lenoir’s “Eisenhower Blues”. (This track, along with the torchy “Poisoned Rose” that follows, featured the one-time rhythm section of Ray Brown and Earl Palmer.) “The Big Light” is a happy hangover song, with a riff borrowed from “Mystery Train” and an overt reference to Merle Haggard in the second verse. And the majestic final trinity of “Jack Of All Parades”, “Suit Of Lights” (which features both the Attractions in their only appearance on the album as well as Elvis’s first use of the f-word on record), and “Sleep Of The Just” provides a magnificent ending to an hour well spent.

King Of America was not a resounding success, and many critics were suspicious of his motives. But Elvis was definitely rejuvenated by the experience, and the album certainly held up in the wake of the alt.country movement at the turn of the century.

With only seventeen minutes of CD time to spare, Rykodisc added just five tracks to the end of their reissue: both sides of the single Elvis and T-Bone released as the Coward Brothers, plus three songs from the sessions—the B-side “Shoes Without Heels”, the outtake “King Of Confidence”, and the stellar demo “Suffering Face”. To make up for it, initial copies included a bonus disc of six songs—five of which were covers, and one of those was a reprise—performed live with several Confederates, including James Burton, T-Bone Wolk, and Jim Keltner.

Ten years later, Rhino had a full bonus disc to work with, and hence found some more nuggets to include along with those extras. “Having It All”, a gorgeous piano ballad, finally got release, along with the reworked “Deportee”, Richard Thompson’s “End Of The Rainbow”, a solo “I Hope You’re Happy Now”, and other demos of album tracks. One more live cover from the same Confederates show didn’t add much, while “Betrayal”, an early draft of “Tramp The Dirt Down” recorded with the Attractions, was also anticlimactic. (They also colorized the cover.)

Two decades after that, the album was chosen for another remastering and expansion in a set dubbed King Of America & Other Realms. This time, six previously unreleased demos—including two songs that would end up on Blood & Chocolate and different verses for “Brilliant Mistake” and “Sleep Of The Just”—were interspersed on a disc with some but not all of the extras from the last two upgrades. A third disc presented most, but again, not all of a performance with the Confederates (now with Benmont Tench on keys) at the Royal Albert Hall three months after the concert sampled earlier. (It also shuffles the setlist as played, and includes none of his solo set.) Along with a lot of James Burton on lead guitar, and different versions of songs we’ve already heard, there are some good renditions of songs from the album, a few covers making their first official appearance in the catalog, and some that would feature one day on Kojak Variety.

Two decades after that, the album was chosen for another remastering and expansion in a set dubbed King Of America & Other Realms. This time, six previously unreleased demos—including two songs that would end up on Blood & Chocolate and different verses for “Brilliant Mistake” and “Sleep Of The Just”—were interspersed on a disc with some but not all of the extras from the last two upgrades. A third disc presented most, but again, not all of a performance with the Confederates (now with Benmont Tench on keys) at the Royal Albert Hall three months after the concert sampled earlier. (It also shuffles the setlist as played, and includes none of his solo set.) Along with a lot of James Burton on lead guitar, and different versions of songs we’ve already heard, there are some good renditions of songs from the album, a few covers making their first official appearance in the catalog, and some that would feature one day on Kojak Variety.

That would have been fine, except he decided that this collection should encompass his larger journey through what we now call Americana, touching on further albums produced by T Bone Burnett and collaborations with various musical icons. Following the lead of the recently upgraded Painted From Memory, he added a pile of songs recorded well after the original album sessions and subsequent promotion, spread throughout three further CDs. And we mean a pile: six songs from The Delivery Man (and two from the Deluxe Edition), four from The River In Reverse, two from Momofuku, five from Secret, Profane & Sugarcane, nine from National Ransom, one from Look Now, and one of the title tracks from Lost On The River. Even “Deep Dark Truthful Mirror” shows up, seeing as it was recorded with Allen Toussaint, and maybe we should be thankful that “Walking On Thin Ice” was overlooked. Other previously released off-cuts included the “Complicated Shadows” demo, “That Day Is Done” with the Fairfield Four, and the timely “April 5th” collaboration with Roseanne Cash and the recently departed Kris Kristofferson.

These are mostly enjoyable tracks, sequenced well, and a deep sampler of his less familiar projects of this century. But these commingled with several items of more recent vintage appearing here for the first time. Three songs came from live DVDs: “Heart Shaped Bruise” in Memphis with Emmylou Harris, and “Bedlam” and “Clown Strike” in Montreal with Toussaint. The alternate of “The Greatest Love” had appeared on the soundtrack of Treme, while “Red Wicked Wine” came from a Ralph Stanley “& Friends” project. A rehearsal of “The Monkey” with Dave Bartholomew and the Dirty Dozen Brass Band is a lot of fun, while “Quick Like A Flash”, an outtake from the New Basement Tapes project, has a very barrelhouse New Orleans feel. Three demos for National Ransom include the unreleased “For More Tears”, a lovely piano and vocal piece. “That’s Not The Part Of Him You’re Leaving” is performed with Larkin Poe in the style of their live arrangement. Finally, there are two lengthier, recent updates of songs from the album. A soulful “Indoor Fireworks” comes from the tour rehearsals for The Boy Named If, while “Brilliant Mistake” is melded with the oldie “Boulevard Of Broken Dreams” in a minor key and dubbed “Cape Fear Version”.

So in order to get the new material, consumers would be purchasing three discs’ worth of music they had already. A condensed version offered the remastered album on one disc plus a seemingly random selection of “highlights” from the other five discs on a second. Had a set merely contained the demos disc and full, uncondensed concert, it would a no-brainer, but at least they didn’t cram two vinyl discs into an already expensive package. Lengthy liner notes from the artist attempt to explain everything, with some stories repeated and a surplus of extraneous commas. Somewhere, Bruce Thomas is smirking.

Elvis Costello and the Attractions The Best Of Elvis Costello And The Attractions (1985)—4½

Current CD availability: none

The Costello Show King Of America (1986)—5

1995 Rykodisc: same as 1986, plus 11 extra tracks

2005 Rhino: same as 1995, plus 10 extra tracks

2024 King Of America & Other Realms: same as 1986, plus 82 extra tracks

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-1850207-1306551329.jpeg.jpg)