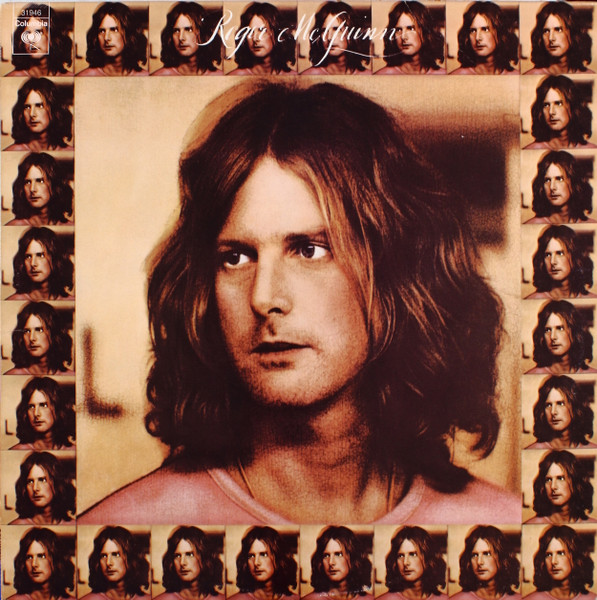

In the ‘70s, you made an album a year, as long as the label was willing to keep you signed. So Roger McGuinn put a band together from some country rock players and recorded Roger McGuinn & Band. It’s a strange package to begin with, as he’s the only person shown on the front cover; they are shown looking down at him from the monitors on the back. But he meant it with the title, because most of the songs were indeed written by his otherwise not-very-notable supporters.

In the ‘70s, you made an album a year, as long as the label was willing to keep you signed. So Roger McGuinn put a band together from some country rock players and recorded Roger McGuinn & Band. It’s a strange package to begin with, as he’s the only person shown on the front cover; they are shown looking down at him from the monitors on the back. But he meant it with the title, because most of the songs were indeed written by his otherwise not-very-notable supporters. The familiar jangle we expect from him is buried on the opening “Somebody Loves You”, a generic rocker, but is lightly picked on his cover of Dylan’s “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door”; Roger himself had played on the original two years before. “Bull Dog” isn’t the first sung he’s sung with a canine lead character, but this one is certainly used in a more menacing way than Old Blue was. “Painted Lady” is a pleasant example of ‘70s soft rock, but it’s not clear why he needed to record another version of “Lover Of The Bayou”, though it certainly kicks.

Calypso isn’t the strong suit of most rock ‘n rollers, so “Lisa” comes off like one of Stephen Stills’ worst ideas, or Jimmy Buffett’s entire catalog, but Roger wrote this all by himself. The keyboard player’s “Circle Song” is basically “Peaceful Easy Feeling” with more dobro and banjo, while “So Long” is another by-numbers highway anthem. Speaking of which, “Easy Does It” may well have been inspired by a bumper sticker he saw, but he manages to make the sentiment work. Another retread closes this side, in this case “Born To Rock And Roll”, last heard on the Byrds reunion album and not much better here.

Any other band might have been proud of Roger McGuinn & Band, but we expect more of Roger McGuinn, with or without a band. He was clearly still finding his way, though it did give work to an up-and-coming producer who would helm future hits by Boston, Charlie Daniels, and Quarterflash, among others. (In a late effort to showcase the band, the expanded CD includes live versions of “Wasn’t Born To Follow” and “Chestnut Mare”.)

Roger McGuinn Roger McGuinn & Band (1975)—2½

2004 Sundazed reissue: same as 1975, plus 2 extra tracks

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-1840949-1416516014-9015.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-4301978-1361153089-3872.jpeg.jpg)