We will admit to having approached Tormato with some trepidation, as its reputation preceded it. For one, that cover—rendered so realistically we always want to grab a sponge and paper towels. The title didn’t help either; puns that lame seemed beneath Yes. (The inner sleeve depicts a topographical map centered on Yes Tor, an actual outcrop in the southwest of England, but that wouldn’t have been a much better title either.) The band seemed to have wanted to forget it too, as it wasn’t made available on CD in the U.S. or Europe until the ‘90s.

We will admit to having approached Tormato with some trepidation, as its reputation preceded it. For one, that cover—rendered so realistically we always want to grab a sponge and paper towels. The title didn’t help either; puns that lame seemed beneath Yes. (The inner sleeve depicts a topographical map centered on Yes Tor, an actual outcrop in the southwest of England, but that wouldn’t have been a much better title either.) The band seemed to have wanted to forget it too, as it wasn’t made available on CD in the U.S. or Europe until the ‘90s. Back then, they had managed to keep the lineup the same, but they were still producing themselves, without Eddie Offord. Musically they’re also keeping up the energy generated on the last album, beginning with the utopian vision of “Future Times”, which is coupled with the separate but similar-sounding “Rejoice”. The suite, and the album as a whole, succeeds when the instrumentalists play with instead of against each other. “Don’t Kill The Whale” is a nice sentiment, of course, but Jon Anderson doesn’t quite have the earnest quality of, say, Graham Nash to pull it off. Plus, the backing borders on disco, especially Chris Squire’s bass effect, which doesn’t suit them. Much better is “Madrigal”, based around a classical-sounding harpsichord with acoustic guitar touches, and much more like their classic sound. “Release, Release” is a call for revolution of sorts, in terms free of metaphor; indeed, the lyrics throughout this album are their most literal yet. A roaring crowd is heard during the drum solo, which seems more than a tad gratuitous, and it only increases once Steve Howe joins in.

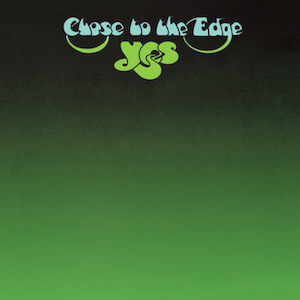

Speaking of literal, “Arriving UFO” describes exactly that, and if you’ve seen the movie, it’s basically a recap of Close Encounters Of The Third Kind; thankfully they don’t use the five-note motif from the film, but they come dangerously close once the ship lands. “Circus Of Heaven” might be close to metaphorical, except that he’s talking about a circus he’d really like to see, with unicorns, centaurs, fairies, and the like. But did he really need to have his young son do commentary at the end? Just as on the first side, “Onward” provides a dreamier interlude in a song of devotion, to a woman, to a higher being, who knows, and it’s quite moving. This and the last track sound most like the Yes people came to hear. “On The Silent Wings Of Freedom” begins with two minutes of that jamming we mentioned, everyone adding flourishes and what sounds like yet another quote of the “Close To The Edge” riff from Steve. But once the vocals kick in everyone starts playing over each other, and there’s just too much going on, until it whips itself into a frenzy and stops.

So Tormato isn’t terrible, just a little full of itself. In addition to the sound supposedly improving, once the album was recognized again as part of the pantheon, it too received expansion the second time the catalog was remastered. Following the B-side “Abilene” and the previously released silly outtake “Money” (rendered unlistenable by Rick Wakeman’s narration) were eight unfinished tracks, some of which would turn up on future Anderson or Howe solo projects. (“Everybody’s Song” would reappear as “Does It Really Happen?” on the next album, but we’re not there yet.) The unlisted “orchestral version” of “Onward” is lovely, but oddly not included was “Richard”, which had been a hidden track on certain cassette and 8-track releases back in the day.

Yes Tormato (1978)—3

2004 remastered CD: same as 1978, plus 10 extra tracks