For some reason Bob decided he needed to sound “contemporary”, which in 1985 translated to a slick sheen over painstakingly constructed backing tracks. (And a shiny Miami Vice jacket too, though he’d been rocking the two-day stubble look for years.) Forget the fact that he worked best on the fly; the songs on Empire Burlesque were repeatedly tweaked so that by the time he got around to finishing the vocals they just didn’t fit. The result was a major letdown.

For some reason Bob decided he needed to sound “contemporary”, which in 1985 translated to a slick sheen over painstakingly constructed backing tracks. (And a shiny Miami Vice jacket too, though he’d been rocking the two-day stubble look for years.) Forget the fact that he worked best on the fly; the songs on Empire Burlesque were repeatedly tweaked so that by the time he got around to finishing the vocals they just didn’t fit. The result was a major letdown.With a Bob-less intro that lasts an interminable twenty full seconds, “Tight Connection To My Heart (Has Anybody Seen My Love)” was an odd choice for a single, and a worse video. “Seeing The Real You At Last” isn’t much better, as it features too many horns and his “soulful” phrasing doesn’t convince. Strip it down to just guitars and we might have something. A near-duet with Madelyn Quebec, “I’ll Remember You” is very sweet, but the noisy if well-intentioned “Clean Cut Kid” kills it, with Ron Wood doing his Keith Richards impressions all the way through. Another attempt at tenderness, “Never Gonna Be The Same Again”, simply tries too hard, with the vocalists mixed too far up front.

Side two is equally frustrating. “Trust Yourself” is something of a riposte to his own “Gotta Serve Somebody”, but “Emotionally Yours” is another hidden gem. The best of the ballads here, it would be a lot better if he’d canned the fake strings, as they distract from the other musicians. (The O’Jays covered this a few years later and gave it a much better reading.) “When The Night Comes Falling From The Sky” got a lot of press for its apocalyptic vision — another epic! the critics raved — but there’s just nothing there save too many instruments shackled to a production familiar from “It’s Raining Men”. (And to make matters worse, it was also picked for a video, and one that would have us believe Dave Stewart of Eurythmics—who happened to be the “director”—was the genius behind the song, as if he came up with the sub-“Watchtower” riff.) “Something’s Burning, Baby” continues the poor use of that epithet in song titles, and mostly staggers along over one chord. Thankfully, the purely unadorned “Dark Eyes” ends the proceedings in best afterthought mode.

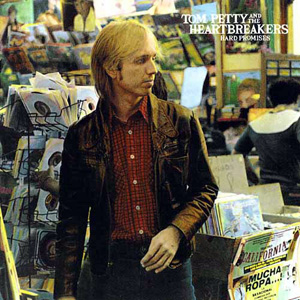

While Empire Burlesque got some praise for its embrace of modern production techniques, even back then it sounded dated. Bruce Springsteen was to comment that if anyone else had written those lyrics (which are reproduced in full on the inner sleeve) they would have been hailed as the next Dylan, but coming from the pen of the original they came off as water treading. Popular dance remixer Arthur Baker is supposedly responsible for the overall sound, but ultimately Dylan should have had the last word. Thirty different names are credited as playing on the sessions, and it’s hard to appreciate these songs for all the extra decorations. With a tighter, smaller set of players in the studio (such as limiting them to Jim Keltner and Tom Petty’s Heartbreakers, hint, hint) these songs could have gotten better care.

Bob Dylan Empire Burlesque (1985)—2½