So much has been written over the years about this album that we hesitate to weigh in. Certainly it’s essential for any fans of the electric guitar; even after everything Eric Clapton accomplished in the ‘60s,

Layla was still a new height for his development, both professionally and creatively.

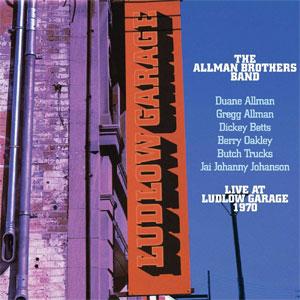

It’s understandably considered a Clapton album—released only three months after his solo debut—but we must remember that Derek and the Dominos were, above all, a band. Clapton and keyboard player Bobby Whitlock collaborated early and often on the album, Bobby’s vocals adding a Sam & Dave-style vibe to the album as a whole. Bassist Carl Radle and drummer Jim Gordon were tight, having played with Delaney & Bonnie (where they met Clapton) and Joe Cocker’s Mad Dogs & Englishmen. All four (along with Dave Mason, seemingly incapable of being in any band for more than a few gigs) worked on George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass, and went off to Florida to record. While there, they crossed paths with the Allman Brothers Band, which is how Duane Allman ended up guesting on the album. (That’s also important to mention: he didn’t play on the whole thing, and only played two shows with the Dominos. He was devoted to his own band and remained so.)

“I Looked Away” is a great opener, and a song that doesn’t get enough attention. All of the elements of the band are introduced here, setting a standard for the four sides. Jim Gordon inverts the snare and kick on “Bell Bottom Blues” in a way no one else do, yet makes it work. “Keep On Growing”, just like “Anyday” on side two, builds a good groove over six and a half minutes, working the guitars and organ nicely against each other. Likewise, “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down And Out” and “Key To The Highway” establish themselves as the modern standard by which these blues standards are known today. If there’s a clunker in the first half, it’s “I Am Yours”, which uses a poetic idea from an earlier century but not as well as the title track, and predicts Clapton’s laid-back style of the ‘70s.

The second half of the album is stellar. “Tell The Truth” finds the stank and stays there, giving Duane plenty of room to soar. “Why Does Love Got To Be So Sad?” builds on a hyper-tense rhythm—with excellent fretwork from Carl Radle—eventually settling into a nice groove for the fade. “Have You Ever Loved A Woman” is another cover, but more fitting with Clapton’s overall theme for the album, that being his infatuation with George Harrison’s wife.

Things absolutely take off on side four. Their epic, keening arrangement of “Little Wing” does to Hendrix’s original what he did to “All Along The Watchtower” (and amazingly, they recorded it before he died). The final cover is the much simpler “It’s Too Late”, which gets its point across much faster than the blues workouts of the other sides. It’s merely a sorbet for the unmistakable riff of “Layla”, a song that’s a classic all its own, but is truly made by Jim Gordon’s gorgeous piano theme (which he stole from Rita Coolidge) over the second half of the track. It is truly one of the finer moments in music. And where can you go from there? Bobby’s solo “Thorn Tree In The Garden” has been compared to “Good Night” following “Revolution 9”, but we think it’s more like having to settle for vanilla ice cream because they ran out of chocolate.

There’s a lot of music on Layla, and the great moments still stand out, even after decades of Classic Rock Radio threatening to kill them off. It’s very possible to make a stellar single LP out of the music here, but that would suggest that the lesser tracks are garbage, which they’re not.

Because of the length, it first appeared as a double CD until the industry caught up to capacity capabilities. It was also the recipient of the first box set devoted to a single album; 1990’s The Layla Sessions served up the album on a single disc, plus a disc of jams with and with the Allman Brothers Band, and another disc of alternate takes. That was for the 20th anniversary; the 40th anniversary brought forth a deluxe edition, with other unreleased tracks, plus songs recorded for their stillborn second album, and the so-called “super deluxe” version, which added an expansion of 1973’s In Concert album to all that. These are all for those with unlimited income; everybody else should stick with the original. On vinyl. Or the single CD, ‘cos it’s convenient.

Derek and the Dominos Layla And Other Assorted Love Songs (1970)—4½

1992 The Layla Sessions: 20th Anniversary Edition: same as 1970, plus 15 extra tracks

2011 40th Anniversary Deluxe Edition: same as 1970, plus 13 extra tracks (Super Deluxe Edition adds another 13 tracks plus DVD)