If you were a white suburban American male, it was a simple rite of passage. On your first day of high school, they gave you your math book, your chemistry book, your gym locker combination, and the newest Rush album. All these things were required to navigate the journey to manhood.

That’s why, like rings on a tree trunk, you can always tell how old someone is by what his favorite Rush album is, give or take a year. If the album you got with your gym locker combination didn’t take, chances are you were converted when you fell in with certain upperclassmen, who would be highly schooled in not only telling you why an older album was better, but possibly how to play some of those spidery riffs.

Like most stereotypes, it’s not an exact science. Plenty of American males, white or otherwise, hate Rush, will tell you why, and refuse any counter-claim. Geddy Lee has an annoying, shrill voice; to today’s ears he sounds uncannily like Gwen Stefani. Neil Peart is an overrated drummer; if he’s so good, he wouldn’t need such a huge kit. Alex Lifeson is a pedestrian guitarist; nothing he’s done is particularly innovative. Their songs suck, and they have no talent—that’s the weakest argument right there, as quality is a matter of opinion, and there is no questioning their technical abilities.

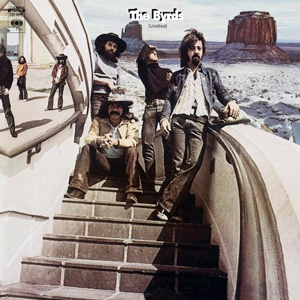

But even the greatest Canadian power trio of all time—sorry, Triumph fans—had to start somewhere, and Rush started without Neil Peart and his dainty prose. Instead, they were a basic heavy rock combo who met in high school, influenced by Cream and Led Zeppelin. Somebody had to sing, so Geddy stepped up, yowling some terribly clichéd lyrics, even by 1974 standards. Mostly the subjects revolve around women and rockin’, both anomalies in their catalog on the whole.

“Finding My Way” is a good place to start the debut, a straightforward driving song, and certainly better than the thankfully short “Need Some Love”. “Take A Friend” has a long fade-in on an arpeggiated riff soon to be appropriated by Spinal Tap, stock echo tricks on the vocal, and an ambiguous message. They’re very insistent that the person who needs a friend should get him slash herself one, but don’t give any pointers on how to achieve that. Things finally slow down for the moody “Here Again”, for seven and a half minutes.

“What You’re Doing” — sadly, not a Beatles cover, but a Zeppelin pastiche musically — pairs the most obvious rhymes in the genre with some tight playing, while “In The Mood”, complete with cowbell, is boogie straight from the notebooks of Lynryd Skynyrd. “Before And After” plays a dreamy instrumental for about three minutes before switching into standard riffing. The big hit was “Working Man”, that indestructible ode to their audience, with solos highlighting everybody and an ending right off the first Zeppelin album.

There are enough elements on Rush that will sound familiar to anyone who came into the party later, which includes just about everybody who’s ever owned a Rush album—Geddy’s voice for one, and some of the guitar flourishes. But they weren’t anything special at this point, and weren’t doing anything that different from, dare we say, Kiss or even Aerosmith at the same juncture. They needed a gimmick, and soon.

Rush Rush (1974)—2½