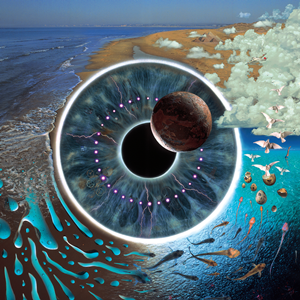

One of the best things to come out of the post-Roger version of Pink Floyd was the re-emergence of Rick (as he was going by now) Wright, in the band onstage as well as in the studio, adding those iconic keyboard touches everywhere. “Wearing The Inside Out” was nobody’s favorite track on

The Division Bell, but it sure was nice to hear his voice again after being silent for so long. Therefore the idea of a solo album coming so soon after the

Pulse live album was certainly appealing.

At least it was until the album came out. Broken China is a dour collection of tracks, half of which have vocals, few of which are upbeat, even the ones with dance rhythms. And for good reason. It was originally intended to be entirely instrumental, but as the overall inspiration was that of a “friend”—later to be revealed as Wright’s wife—being treated for clinical depression, he felt words and vocals would be needed. The musicians are top-notch, of course, with Floyd auxiliaries Anthony Moore (who wrote most of the lyrics, and it turns out the wife’s therapist did some too) and Tim Renwick, plus Dominic Miller, Pino Palladino, Manu Katché, Kate St. John, and a special vocalist on two tracks. When he himself sings, he predicts the 21st century timber of Brian Eno’s voice.

The album is presented in four parts, the first representing childhood, illustrated by a teddy bear with its head nearly torn off. “Breaking Water” is a mostly ambient track used as an introduction, much like the last two Floyd albums. There’s a startling switch to the “Humpty Dance”-style backing track for “Night Of A Thousand Furry Toys”. Moore literally phones in a vocal, and somehow a music box tinkles its way into the mix at the end. The very somber “Hidden Fear” moves into the mechanized sound of “Runaway”, composed solely by Moore, who apparently did the programming.

We move to adolescence, supposedly, which is mostly instrumental. “Unfair Ground” is another ambient transition, but we don’t need that fairground sample (already heard in “Poles Apart”) inserted for some reason. “Satellite” is a lengthy showcase for Tim Renwick, which seems to get edgier and edgier until Rick comes into sing “Woman Of Custom”. The chorus redeems the song, with subliminal harmonies from Pino’s wife, who used to back up Paul Young. “Interlude” is a slow piano piece, and welcome.

Part three apparently involves depression directly, as hinted at by the pointedly eerie “Black Cloud”, and “Far From The Harbour Wall” piles on the sadness with frank lyrics and minimal metaphors. The mostly ambient “Drowning” intensifies it, but Sinéad O’Connor gives voice to “Reaching For The Rail”, sung in first person, with Rick providing sympathetic counterpoint in his own verse and in the last.

The final segment addresses resolution, and there is indeed some relief here. “Blue Room In Venice” is more of an interlude than the verses would suggest, but he’s started to let his voice reach higher notes. “Sweet July” is mildly majestic, with Gilmour-style guitar (no, still not him) and rolling cymbals matching the cavorting dolphin in the booklet. The energy of “Along The Shoreline” can’t help but recall “Run Like Hell”, and we’d like to say it represents a “Breakthrough”, but that’s the title and theme of the final track, a more contemplative but still powerful statement sung by Sinéad. (Six years later, Rick would sing this onstage with Gilmour.) And with that, the album ends.

We haven’t found any documentation as to whether Broken China actually helped anyone suffering from depression, but that’s none of our business. It’s not a Pink Floyd album, so its appeal outside the fanbase is fleeting and limited. We have found its charms; proceed with caution.

Rick Wright Broken China (1996)—3

Still one of the hardest working men in the business, Jack Grace’s latest album confirms his deserved title as reigning Martini Cowboy. Drinking Songs For Lovers was quietly released last year, as might be expected for an indie release, but was immediately hailed by legendary New York City deejay Vin Scelsa for its excellence. Not bad for a year full of sensory overload.

Still one of the hardest working men in the business, Jack Grace’s latest album confirms his deserved title as reigning Martini Cowboy. Drinking Songs For Lovers was quietly released last year, as might be expected for an indie release, but was immediately hailed by legendary New York City deejay Vin Scelsa for its excellence. Not bad for a year full of sensory overload.

.png)