As a youth in Belfast, Van Morrison was obsessed with jazz and rhythm & blues, but by the time bands like his were getting noticed, record companies were looking to jump on the British Invasion bandwagon. So over the two years and two dozen players who passed through their ranks, Them were tasked with making hit singles out of their brand of British R&B—kinda like the Animals. Producer and songwriter Bert Berns came over from New York to cash in, sometimes using one Jimmy Page to bolster the studio sound.

As a youth in Belfast, Van Morrison was obsessed with jazz and rhythm & blues, but by the time bands like his were getting noticed, record companies were looking to jump on the British Invasion bandwagon. So over the two years and two dozen players who passed through their ranks, Them were tasked with making hit singles out of their brand of British R&B—kinda like the Animals. Producer and songwriter Bert Berns came over from New York to cash in, sometimes using one Jimmy Page to bolster the studio sound. Somehow the Van-penned B-side of “Baby Please Don’t Go” became a huge hit (and garage band staple) on both sides of the pond, and since America was all about hits, “Gloria” was emblazoned on the cover and among three single sides added to the distillation of the excellently titled British album The Angry Young Them. It was placed at the end of side one, which began with Berns’ “Here Comes The Night”, another hit with a distinct Sam Cooke influence in the vocal. Berns also foisted “Go On Home Baby”, which features rare harmonies from another band member, on them. John Lee Hooker’s “Don’t Look Back” is a cool ballad with tasty piano, and the prominent organ of “I’m Gonna Dress In Black” makes it very much an Animals soundalike. “(Get Your Kicks On) Route 66” had already been claimed—and nailed—by the Stones.

Of Van’s own songs, “Mystic Eyes” is the standout, basically a two-chord jam with a seemingly extemporaneous recital that’s a forerunner to his later, longer ruminations. (“Little Girl” isn’t as successful, and “One Two Brown Eyes” is more notable for its slide guitar effects.) “One More Time” and “If You And I Could Be As Two” are attempts at seduction, stuck between belting and speaking, and “I Like It Like That” mostly meanders.

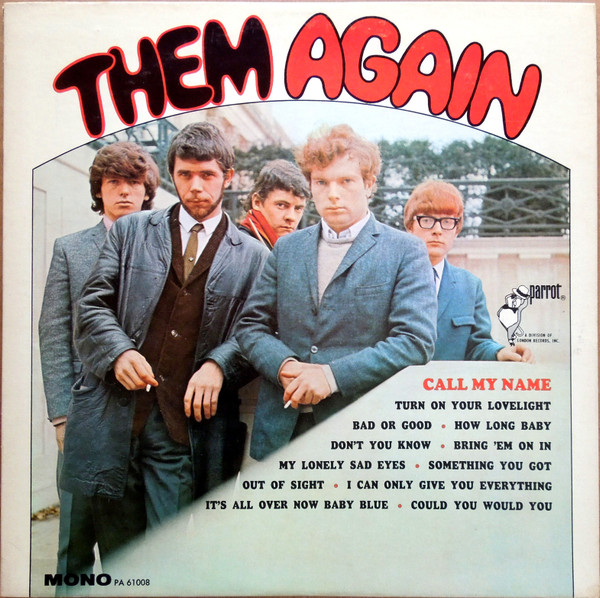

Less than a year later, Them Again shaved the British version down to twelve tracks, still split between Van originals and covers. Of these, their moody take on Dylan’s “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” is the clear winner. Chris Kenner’s “Something You Got” has a sax solo that might be Van, and these days it’s interesting to hear “Turn On Your Love Light” and consider that Them’s version could be what inspired the Dead to do it. “I Can Only Give You Everything” is a trashy variation on the usual garage riff, and “Out Of Sight” is the closest they got to being James Brown. Tommy Scott was now their producer, so four of his songs made the album. “Call My Name” and “How Long Baby” are rather ordinary, but “I Can Only Give You Everything” has a cool snotty riff, and the flute and piano on “Don’t You Know” predict “Moondance”.

Less than a year later, Them Again shaved the British version down to twelve tracks, still split between Van originals and covers. Of these, their moody take on Dylan’s “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” is the clear winner. Chris Kenner’s “Something You Got” has a sax solo that might be Van, and these days it’s interesting to hear “Turn On Your Love Light” and consider that Them’s version could be what inspired the Dead to do it. “I Can Only Give You Everything” is a trashy variation on the usual garage riff, and “Out Of Sight” is the closest they got to being James Brown. Tommy Scott was now their producer, so four of his songs made the album. “Call My Name” and “How Long Baby” are rather ordinary, but “I Can Only Give You Everything” has a cool snotty riff, and the flute and piano on “Don’t You Know” predict “Moondance”.

Van himself was limited to four songwriting credits. “Could You, Would You” with its powerful drum fills opened the album, and the double acoustic guitar on “My Lonely Sad Eyes” almost makes it folk-rock. “Bad Or Good” is nice and soulful, just as “Bring ‘Em On In” is defiant.

Management issues and general disinterest led to the band splitting into factions on tour, and ultimately Van went off to be a solo artist of merit, which meant that various repackages of Them material popped up throughout the ‘70s. The first, 1972’s Them… Featuring Van Morrison, excerpted ten songs from each of the American albums but in reverse order, with dense liner notes by Lester Bangs in phone book-size type across the inner gatefold. Two years later, Backtrackin’ helpfully offered up ten tracks that weren’t on either of the American albums, including such singles as “Baby Please Don’t Go” and their cover of Simon & Garfunkel’s “Richard Cory”, as well as “Hey Girl” (another flute-laden precursor to “Cyprus Avenue”) and the previously unreleased “Mighty Like A Rose”. Three years after that, The Story Of Them offered nine more of the same, mostly blues covers but also the rare title track, a rambling memoir in changing keys originally split over two sides of a single but here continuous, the early EP track “Philosophy”, and the lovely late single “Friday’s Child”.

Eventually, The Best Of Van Morrison included “Gloria”, “Baby Please Don’t Go”, and “Here Comes The Night”; Volume Two offered “Don’t Look Back” and “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” amidst songs from the ‘80s simply because Polydor still had the rights to them. Another attempt to tell The Story Of Them Featuring Van Morrison on two CDs had to navigate mono mixes and stereo remixes, and still seemed to be somewhat random in its sequencing. It wasn’t until the band’s 50th anniversary (and Van’s partnership with Sony Legacy) that The Complete Them 1964-1967 presented a full chronological overview, with all of the singles and album tracks in context on two discs, and a third devoted to previously unreleased demos and select alternate takes and BBC sessions. Van even wrote the liner notes. Getting to hear the singles in release order doesn’t take away the haphazard construction of the albums, even in the British sequences, but we do hear his voice and songwriting improve.

Them Them (1965)—3

Them Them Again (1966)—3

Them Backtrackin’ (1974)—2½

Them The Story Of Them (1977)—2½

Them The Complete Them 1964-1967 (2015)—3

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-17614705-1614647202-8527.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-2944169-1308479357.jpeg.jpg)