Like most hungry London-based performers, The Jimi Hendrix Experience made multiple appearances on the BBC’s handful of radio shows that focused on current pop music. And like most people who went on to be world-famous, many of those performances were spread around via bootlegs until legitimate releases happened.

The first such release came courtesy of Rykodisc. Radio One presented 17 tracks, split between hits and more unique performances. As with most BBC collections, fanatics had lots to pick apart, while the more casual fan could gravitate towards markedly alternate versions of songs they knew from the albums, along with those that were, well, new. “Killin’ Floor” was constant in his setlists, and cooks here. The blues chestnut “Catfish Blues” appears in its then-first known performance (complete with a nod to “Rollin’ And Tumblin’”), as does “Hear My Train A-Comin’”, with unfortunate “party” noises, which also mar “Spanish Castle Magic”. “Driving South” was an excuse to jam, and comes from a show hosted by British blues legend Alexis Korner, who also plays slide with the band on “Hoochie Koochie [sic] Man”. Jimi even composed a “Radio One Theme” for one show.

These performances took place throughout a very busy 1967, when the band played a lot of shows and had the tightness to prove their worth. Save the occasional handclap or vocal overdub, these are live performances, and prove Jimi was able to create his own pyrotechnics without the multitracking that would soon dominate his regular studio work. Thus “Burning Of The Midnight Lamp” is a simpler trio version, without all the decorations the single/album track got. Of course, one must take the good with the bad, so while his funky arrangement of “Hound Dog” has merit, the overdubbed barking makes it one to skip. Better backing vocals are on their cover of “Day Tripper”, which does not include John Lennon, no matter what anybody tells you.

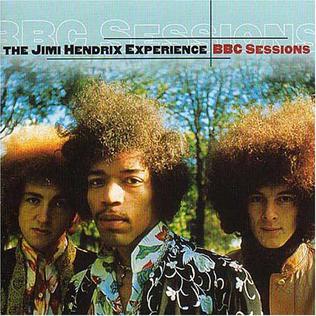

Ten years later, once the “family” gained control of the masters, an expanded double-disc set more directly titled

BBC Sessions presented virtually everything he recorded for the station, including alternate takes from the same shows, presented in a not-quite-chronological order to cut down on repetition. This is good, since we get two more versions of “Driving South” and another “Hear My Train A-Comin’” (this one with “support” vocals). Even with the retreads, they did find more rarities, like his one-time-only cover of Dylan’s “Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window?” And that really is Stevie Wonder playing drums on the extended jam that leads into his own “I Was Made To Love Her”.

Of historical importance, the set ends with the band’s notorious performance on the Lulu TV show, when they cut short “Hey Joe” (which had been requested by the hostess herself) to go into “Sunshine Of Your Love” in “tribute” to the recently disbanded Cream, who’d written the song with Jimi in mind in the first place. And it’s just as well, since there are two other, similar takes on “Hey Joe” elsewhere in the set.

Because the BBC never saved anything, the sound quality on both is a little muddy, and the tweaking modern-day producers took to make the new set less mono doesn’t help. But as a companion to the three true Experience albums, and in balance with some of the other post-Experience recordings we’ll get to soon enough, BBC Sessions is a worthy addition to one’s Hendrix pile. (It was eventually re-released once Sony took over the Hendrix catalog, with the addition of another “Burning Of The Midnight Lamp” and a DVD with a documentary. They also released a single-disc version, but what’s the point?)

The Jimi Hendrix Experience Radio One (1988)—3½

The Jimi Hendrix Experience BBC Sessions (1998)—4

2010 reissue: same as 1998, plus 1 extra track (and DVD)