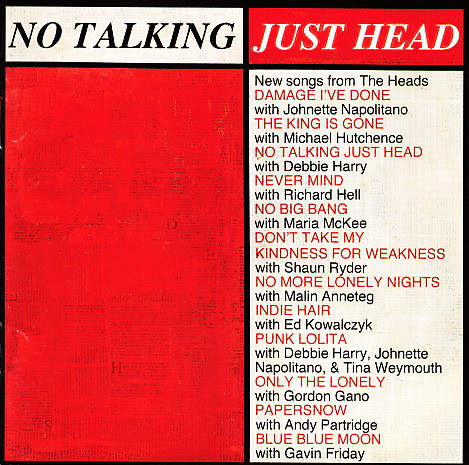

The members of Talking Heads had grown tired of waiting for David Byrne to deign them with his presence again, so after five or so years they began recording together. Chris Frantz, Jerry Harrison, and Tina Weymouth had stayed busy producing other people, so they had several singers they could ask to sing for them, along with old friends from their CBGB days, when they started making music together again. Byrne had other ideas, and tried to sue them; the eventual project was credited to The Heads, with the album pointedly titled No Talking, Just Head.

No matter how they approached it, the deck was stacked against them. Sometimes an established band can find a new singer to take them to commercial heights, but not every band is AC/DC. Rather than sticking with one collaborator, the Heads assigned each of the 12 tracks on the album to somebody different. Each of the resulting songs is so different, it sounds like a mix tape of 12 different bands.

Johnette Napolitano of Concrete Blonde opens with the dark “Damage I’ve Done”, and would go on to tour with the trio to promote the album. Michael Hutchence of INXS (who would have their own issues trying to replace a singer) ironically makes one of his last appearances on an album on “The King Is Gone”, and Blondie’s Debbie Harry wails the profane title track. “Never Mind”, which seems to be based around the drums for their version of “Take Me To The River”, is a showcase for Richard Hell, while the frenetic “No Big Bang” is an odd pairing for the otherwise soulful Maria McKee. Shaun Ryder gets to do his Happy Mondays thing all over “Don’t Take My Kindness For Weakness”.

A still-unknown spoken word performer named Malin Anneteg recites the strange lyrics for “No More Lonely Nights”, while the singer from Live was still coasting on their hit album when he added “Indie Hair”. “Punk Lolita” might be the highlight of the album, with Debbie, Johnette, and Tina Weymouth trading fun rap-influenced vocals just like Tom Tom Club. Gordon Gano of Violent Femmes is lost in the mix of “Only The Lonely”, but there’s no mistaking Andy Partridge on “Papersnow”. Finally, cult figure Gavin Friday warbles “Blue Blue Moon”.

While Chris, Jerry, and Tina were all undoubtedly key to the success of Talking Heads, and contributed to the sound of the band, David Byrne’s vocals and lyrics were what resonated in millions of album sales. This goes both ways, as Byrne’s solo albums are nearly devoid of any music that sounds like the old band. No Talking, Just Head remains a curio, more interesting for fans of the individual singers.

The Heads No Talking, Just Head (1996)—2