You can’t argue with math, so it really had been ten years since Elvis Costello’s last album with the Imposters, and only his fourth album of “new” material in that same span.

Look Now arrived in something of the wake following a tour that focused on 1982’s

Imperial Bedroom (a big favorite around these parts) as well as work with Burt Bacharach on more songs for a projected Broadway musical based on 1998’s

Painted From Memory. Both albums show up in all the press for this one, but we hear shades of

Mighty Like A Rose in the baroque horn arrangements, and

Punch The Clock in the female backup vocals. One thing the album doesn’t do is rock; the spirit, as well as the musical and piano contribution, of Bacharach looms large over the proceedings, which tend mostly toward soulful pop. (For another clue,

Dusty In Memphis gets a clever acknowledgment in the notes.)

The big drums and sound of “Under Lime” are about as loud as the album gets, a catchy sequel of sorts to “Jimmie Standing In The Rain” with a plot that gets more disturbing with every listen. “Don’t Look Now”, written with Bacharach, is just one of many songs sung from a woman’s perspective, this one bringing to mind either an aging ingénue or a young model. It’s pretty, yet brief. “Burnt Sugar Is So Bitter” is a collaboration with Carole King that sat unheard from the ‘90s; while it’s hard to discern her mark, the theme of a spurned divorcée is carried over in “Stripping Paper”, something of a cousin to “This House Is Empty Now”, wherein the narrator finds the remnants of her marriage amid the décor. The “daring” teen pregnancy ode “Unwanted Number” makes a surprising appearance, being the other song he contributed to the soundtrack of Grace Of My Heart, the film that brought him together with Bacharach in the first place. We take a break from female problems to world issues, as “I Let The Sun Go Down” is concerned with the impending Brexit.

The modern-sounding “Mr. & Mrs. Hush” bears the most echoes of his collaboration with The Roots, and catchy as it is, still befuddles the listener still trying nail the identities of Harry Worth, Mr. Feathers, Stella Hurt, and the like. “Photographs Can Lie” is another Bacharach co-write, this time from the point of view of a woman considering her father’s infidelities. Things pick back up in “Dishonor The Stars”, which deftly sets up the soul promise made real in “Suspect My Tears”, another 20-year-old tune making its welcome appearance, with a terrific Hey Love arrangement and occasional falsetto. (Nobody told him he lifted the chorus from Diana’s version of “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough”.) “Why Won’t Heaven Help Me?” continues the R&B revue, with a samba backing and clever interlocking vocals. It makes “He’s Given Me Things”, the final scorned woman tune written with Burt, something of an anti-climax; it’s a little too quiet, and we’re left wondering if all these women are the same character.

Because it had been so long, Look Now is a big deal, with a lot of expectation for it. The history of some of the compositions puts it across not so much as a statement but a reason to give these songs some exposure past the concert stage, where he’s been living for most of the decade. The diehard fans will also eat up the Deluxe Edition, with four extra tracks: “Isabelle In Tears” sounds like an unfinished audition for Bacharach; “Adieu Paris”, a smarmy excuse to write and sing in lounge French; “The Final Mrs. Curtain”, a decent contender for the album proper if not for the Hush couple; and “You Shouldn’t Look At Me That Way”, written for the movie Film Stars Don’t Die In Liverpool.

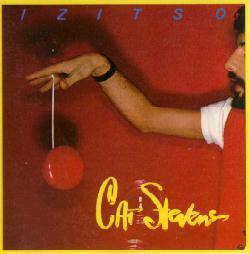

But that cover art? He’s a much better songwriter than a painter.

Elvis Costello & The Imposters Look Now (2018)—3

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-4164441-1357411349-7909.jpeg.jpg)