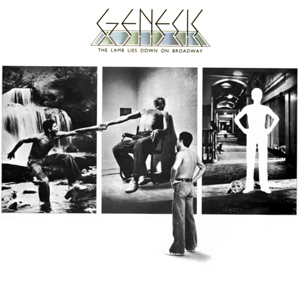

Of all of the mysteries that have plagued man since the dawn of recorded sound, one of the most baffling by far would have to be the simple question: “What the hell is

The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway about”? Somehow the briefest answer (“94 minutes”) doesn’t satisfy those seeking a succinct plot summary.

Those already familiar with Genesis albums to date would already know that the band’s songs rarely followed any clear-cut scenario, being fantastically surreal and multi-dimensional. Still, this being the band’s first double LP, with all the suggestion of a concept album about an individual’s personal and/or allegorical quest (Tommy, Quadrophenia, etc.), the listener really wants to know what’s happening over the course of 23 shorter tracks (by Genesis standards). Peter Gabriel was always more of a poetic writer than the narrative Pete Townshend, so wordplay adds further dimension and distraction. The original album featured a lengthy essay inside the gatefold, which needed to be ingested concurrently with the lyrics printed on each disc’s inner sleeve. (Those who bought the cassette or 8-track were even further up a creek.)

The Interwebs provide lots and lots of interpretations, and all make sense in their own ways, no matter how outlandish or comical. The story within The Lamb is moot if the music isn’t any good, but it is. The title track opens with cascading piano figures that will continue most of the track, structured in best verse-chorus-bridge format, providing something of a grand opening number to this particular Broadway show, pun intended. Introducing the hero, a street rat named Rael (coincidentally, a name previously used for an aborted Townshend “opera”), we can see him roaming the Manhattan streets as the opening credits roll, pausing to contemplate the titular lamb in its repose. A quote from “On Broadway” (less than a year after Bowie’s use of it) winds down into “Fly On A Windshield”, wherein “the wall of death” threatens Rael, its pastoral melody giving way to a crashing march, and “Broadway Melody Of 1974”’s litany of pop culture and historical collisions. “Cuckoo Cocoon” is another lilting air, with flute solo, depicting Rael in whatever state of animation he’s found, before he ends up “In The Cage”. Here we find the first appearance of Rael’s brother John, who appears to be even more of a selfish prick than Rael himself. John leaves him spinning in said cage, and Rael wakes up to observe “The Grand Parade Of Lifeless Packaging”, humanity reduced to objects on a factory conveyor belt. One such object is, whaddya know, John.

Rael retreats to memories of life “Back In NYC”, via another infectious 7/4 meter, and the time a porcupine compelled him to shave his heart clean of hair (no, really), accompanied by the gorgeous instrumental “Hairless Heart” (told you), which brings upon the next memory of “Counting Out Time”, or navigating his first carnal encounter by way of a sex manual. It’s a silly but fun song, highlighted by the wobbly treated guitar solo and falsetto descants. The music from the bridge of the title track heralds “The Carpet Crawlers”, another wonderful track that through a combination of vocal pitch and mixing builds so well from quiet to immersive. Said crawlers are searching throughout “The Chamber Of 32 Doors”, only one of which (supposedly) won’t lead back inside said chamber. The song itself does seem to sum up the main theme of the album (the search for enlightenment), and the major resolution of the very last chord nicely cues the curtain, intermission, change the record, tape, or CD.

Act two crashes in with “Lilywhite Lilith”, an old blind woman who asks Rael to help her through the chamber. She directs him to “The Waiting Room”, illustrated by a scary collage of noises through keyboards and guitars, finding release into an instrumental jam. “Anyway” features more cascading piano arpeggios, with some musical theater overtones, as Rael waits for death to arrive in the form of “The Supernatural Anaesthetist”, who comes and dances around to another precise instrumental. Having seemingly survived, Rael enters another cave to find “The Lamia”, three serpents with female head and torso, summoning him from a pool, and we have another patented Gabriel multisexual encounter, accompanied by a beautiful piano. The serpents bite Rael and promptly die, whereupon he, heartbroken, eats them. (No, really.) A stirring ambient instrumental, “Silent Sorrow In Empty Boats”, gets its title from a line in “The Lamia”.

Rael gets another punishment for his sensual indulgences when he finds himself in “The Colony Of Slippermen”, grotesque creatures transformed into their current bulbous state by encounters with those very same Lamia. He finds John there too, and the only way they can transform back from Slipperman form to human appearance is to have their tallywackers removed. (No, really.) And they do, getting to keep them as a souvenir in a tube. Sadly, a raven swoops down and steals Rael’s, he asks John to help him catch it, but John refuses and abandons him again. Rael searches for the bird along a “Ravine”, another vivid, impressionistic instrumental, only to watch the raven drop the tube in the water below. Suddenly, he catches a glimpse, through the rocks, of home, as “The Light Dies Down On Broadway”. He moves to go there, but what’s this? John is drowning in the river! Rael goes to rescue him to the funky sounds of “Riding The Scree”, and struggles to save him “In The Rapids”, first floating quietly then building as he manages to grab his brother and pull him to safety. He looks down to see not John’s face but his own. (Yes, really.) A siren heralds “It”, italics intentional, the big finale, resolving everything and nothing.

Whew. The Lamb is a lot to take in, and despite all its annotation, is best experienced tangentially rather than directly. The best songs stand on their own outside the album—the title track, “It”, all of side two, most of side three—and musical themes do recur—the title track, the end of “Back In NYC”, the chorus of “The Lamia”—tying things together like a concept album should. Although Gabriel is center stage, the band’s contributions are not to be ignored; we can’t say enough about Phil Collins’ drumming. Another key contributor was Brian Eno, credited with “Enossification”, likely treating some of the sonics in his own special way. And with that, an era came to a close, both in the band and prog in general.

Fifty years on, the album finally got the big box treatment, with a Super Deluxe Edition containing the remastered album and the live recording first issued with overdubs in Genesis Archive, but now restored (albeit still with overdubs) with the encores that weren’t in that set. A Blu-ray disc had all the music in hi-res and Dolby Atmos, while three early band demos were included via download access only. And of course, a nice book.

Genesis The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway (1974)—4

2025 Super Deluxe Edition: same as 1974, plus 25 extra tracks (and Blu-ray)