It’s been a lot of fun for us so far, and we look forward to keeping up the pace over the next 52 weeks and beyond. While we intend to keep consistent with our brand, we plan to continue widening the scope of what we offer. So as always, thanks for reading, and please keep sending comments (and complaints). And of course, please tell your friends and musically inclined acquaintances about Everybody’s Dummy. We are truly grateful for the attention.

"I'm nobody's dummy. I'm everybody's dummy. I believe everything I read, see, and hear." -- Lester Bangs

Saturday, February 28, 2009

Has it really been a year?

Friday, February 27, 2009

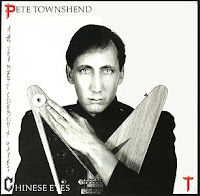

Pete Townshend 4: All The Best Cowboys Have Chinese Eyes

Pete came close to killing himself by the end of 1981 with a spiraling addiction to alcohol, cocaine, heroin and just about everything else, but managed to survive in time to remember what he was here for. He wrote songs and recorded demos before, during and after his rehab, and emerged with a new mod haircut and an album with the unwieldy title of All The Best Cowboys Have Chinese Eyes. Many have suggested that it’s no great shakes, but this author has to disagree; while the Who struggled to remain relevant, Pete was able to express himself and his neuroses and make music that worked.

Pete came close to killing himself by the end of 1981 with a spiraling addiction to alcohol, cocaine, heroin and just about everything else, but managed to survive in time to remember what he was here for. He wrote songs and recorded demos before, during and after his rehab, and emerged with a new mod haircut and an album with the unwieldy title of All The Best Cowboys Have Chinese Eyes. Many have suggested that it’s no great shakes, but this author has to disagree; while the Who struggled to remain relevant, Pete was able to express himself and his neuroses and make music that worked. An interest in writing short stories and prose rears its head with the opening track. “Stop Hurting People” takes an extended poetry reading and matches it with a triumphant arrangement. (He was, after all, pursuing a side job as a book editor.) “The Sea Refuses No River” wraps itself around a hypnotic theme, then goes into a wonderful middle section with a very well constructed guitar solo. “Prelude” is a half-finished idea that slides into “Face Dances Part Two”, the title track that never was, and something of a hit despite its 5/4 meter. “Exquisitely Bored” is a very LA tune, likely written during his recovery, beaten out of the way by the verbal barrage of “Communication”.

“Stardom In Acton” is similar to “Exquisitely Bored” without being repetitive. The title refers to the section of London where the Who started out, though first listens and even the current CD misspell it “action”. “Uniforms” manages to distill Jimmy’s central crisis in Quadrophenia into three minutes successfully, and there’s that melody from “A Little Is Enough” sneaking in over the bridge. “North Country Girl” is a poor rewrite of the folk song, moved aside by “Somebody Saved Me”, which goes through some personal vignettes that reveal with every listen. The album ends with perhaps Pete’s best-ever song, the haunting “Slit Skirts”. The words ache to mean something, and despite the plot the chorus does a splendid lift to another key each time. The song fades out much too fast. (The take in the video is longer and has a different vocal, plus a harmonica solo from Peter Hope-Evans. We also get to see the rhythm section of Tony Butler and Mark Brzezicki, shortly of Big Country, who positively shine throughout the album.)

Chinese Eyes is a great album, especially for 1982, when many of his contemporaries would start to lose the plot. The upgraded CD added three tracks, but as is often the case, they don’t live up to the rest of the album. The underwhelming “Vivienne” is interesting to hear if only because it came that close to making the original, while “Man Watching” and “Dance It Away” were contemporary B-sides, the latter sounding the most like the Who, coming as it did out of a live jam.

Pete Townshend All The Best Cowboys Have Chinese Eyes (1982)—4

2006 remaster: same as 1982, plus 3 extra tracks

Wednesday, February 25, 2009

CSN 7: American Dream

Nice of him, but he shouldn’t have. Really.

American Dream is a big step back from the strides Neil had made of late, and his presence and participation doesn’t seem to inspire the other three any. Nearly every track suffers from contemporary production, even Neil’s title track with its a silly synth flute line and sillier video. As bad as it is, it’s one of the better songs on the album. But it’s not as good as “This Old House”, which came out of the Farm Aid mindset and would probably have been received better had it come out in the context of his 1992 project, but we’re getting ahead of ourselves. “Feel Your Love” isn’t horrible, but deserves better lyrics, and “Name Of Love” is just ordinary, with an ill-advised call-and-response motif.

Nash cries sad tears about the environment and its neglect by governments (“Shadowland”, “Clear Blue Skies”, the excruciating “Soldiers Of Peace”) except for “Don’t Say Goodbye”, which sees him alone at the piano with a lead guitar break from Stills. As for Crosby, he’s just glad to be alive. Per usual, he brought two songs to the table. “Nighttime For The Generals” is loud and angry, but not very convincing. The big focus, rather, was on “Compass”, where he directly addresses his struggles with addiction and subsequent imprisonment. It has the potential to be embarrassing, but the delivery and exquisite production make it succeed.

Stills doesn’t dominate the proceedings for once, letting his guitar do the talking when Neil’s isn’t. But he’s just as insufferable as ever, giving “Got It Made” and “That Girl” mushmouthed deliveries and yacht rock arrangements. “Drivin’ Thunder” is a collaboration in credits only with Neil, as is “Night Song”, which is the most welcome song here, as it’s the last one in a program over an hour long. (It would turn up again on Neil’s next album, but rewritten, and without Stills’ input on the track or the writing credits.)

If we really expected a miracle, we were only kidding ourselves. Basically Neil let them use his ranch and choose their own rhythm section, and thus American Dream ended up as the bare minimum. It’s clear his mind was elsewhere, and was a rare case of him actually making good on a promise to people who ultimately needed him more than he did them.

Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young American Dream (1988)—1½

Monday, February 23, 2009

Elvis Costello 26: Momofuku

All this speculation—which wasn’t helped by initial reports that it would only be available on vinyl—was moot when we finally got to hear the music. The songs were recorded as quickly as they were written, with the two notable exceptions being collaborations with Roseanne Cash and Loretta Lynn. The Imposters provide the backbone, while a handful of young musicians a couple of generations removed fill out the sound without getting in the way.

After the smoother pop and jazz elements of the last couple of albums, this time it’s mostly back to the welcome clamor he played so well. “No Hiding Place” is a great opener, pointing a not-so-subtle finger at those Internet sleuths. “American Gangster Time” follows with more political anger, and from there the noise becomes a matter of taste. The least successful tracks attempt to pull puns out of names (“Stella Hurt”, “Harry Worth”, “Mr. Feathers”) and fail to connect, but it’s the comparatively gentler songs that win here, from “Flutter And Wow” with its shades of Brian Wilson, the tender apology and lullabye of “My Three Sons” and the haunting “Song With Rose”.

He was starting to take his sweet time between albums again, but it was clear that like the elder statesmen he was beginning to emulate, when he felt like saying something, it was worth hearing, and on that level, Momofuku didn’t disappoint. Since he was insisting that his income came from live performances and not from album releases anymore, we could only guess when we’d hear from him again.

Elvis Costello and the Imposters Momofuku (2008)—3½

Friday, February 20, 2009

Paul McCartney 13: Tug Of War

It was worth the wait. Right from the start Tug Of War was his best album in years. The title track is sneaky, an instant classic for those who heard it. The plaintive little melody takes its time to make its point, with just a hint of strings. The middle section is breathtaking. The tossed-off “Take It Away” was a moderate video-driven hit, and another one of Paul’s portraits of a working musician. The end section shows off the layered vocal stylings of new collaborator Eric Stewart, formerly of 10cc. “Somebody Who Cares” was inspired by the aftermath of John’s murder, and is quite empathetic without being condescending. “What’s That You’re Doing” is the lesser collaboration with Stevie Wonder (more on that later) and doesn’t work after the first playing. “Here Today” is overtly about John, and gets one misty to this day. This is exactly the type of tribute one would expect from Paul’s capabilities.

“Ballroom Dancing” is a great production, even with all the horns, with that pounding piano driving the train. “The Pound Is Sinking” doesn’t seem to be about much, though its two bits are soldered together okay. “Wanderlust” also has two melodies spiraling together but much more successfully, and is quite evocative of the sea. Paul’s old hero Carl Perkins helps with “Get It”. It’s not the best idea for a duet, but the laughter at the end is infectious. The “Be What You See” link doesn’t need a separate listing, but “Dress Me Up As A Robber” has its moments amidst all the disco rhythms. “Ebony And Ivory” was the big single, the call for racial harmony with Stevie Wonder. It’s something of an anticlimax after all the great music that’s come before, and its sentiments, while genuine, have turned to self-parody over time.

Tug Of War wasn’t really an all-star album, but having such big guns as Carl, Stevie and other old friends was good luck. It got raves at the time, and would have even without all the help. The songs stand up and the production didn’t get in the way. That didn’t stop him from remixing the album for its 2015 reissue, which didn’t ruin it; the 1982 mix was still available to those who bought the pricey deluxe box. Along with several solo demos, three contemporary B-side made their overdue appearance: the Celtic-flavored strum “Rainclouds”, “I’ll Give You A Ring”, and a mix of “Ebony And Ivory” sung by Paul alone. These don’t detract at all from Tug Of War being his best album in years. Back in the day, we simply hoped he could keep up the pace.

Paul McCartney Tug Of War (1982)—3½

2015 Archive Collection: same as 1982, plus 11 extra tracks (Deluxe Edition adds another 12 extra tracks and DVD)

Thursday, February 19, 2009

Ringo Starr 9: Stop And Smell The Roses

After limping through the end of one decade, Ringo was determined to start the ‘80s on a high. First, he took a starring role in the unfortunate prehistoric comedy Caveman, which did have the indisputable bonus of introducing him to actress Barbara Bach, to whom he is still married to this day. Then he set to reviving his recording career just like he did in 1973: by asking his former bandmates and a few other famous friends for help. (John’s murder meant only two other ex-Beatles would be involved in the finished product.) He even played the drums on every track.

After limping through the end of one decade, Ringo was determined to start the ‘80s on a high. First, he took a starring role in the unfortunate prehistoric comedy Caveman, which did have the indisputable bonus of introducing him to actress Barbara Bach, to whom he is still married to this day. Then he set to reviving his recording career just like he did in 1973: by asking his former bandmates and a few other famous friends for help. (John’s murder meant only two other ex-Beatles would be involved in the finished product.) He even played the drums on every track. By the time the album was ready, the label that put out Ringo’s last album lost interest, so he ended up on another new imprint that happened to be founded by the guy behind Casablanca Records. Even they forced him to change a few songs (just as what had happened to George) as well as the original title of Can’t Fight Lightning before Stop And Smell The Roses finally appeared to much fanfare.

Paul’s first contribution, the inoffensive if tossed-off “Private Property”, opens the album, with lots of sax from Howie Casey and Linda on harmonies. (Of course, by the time the album came out Wings had been disbanded. Adding insult to injury, Laurence Juber’s name was misspelled three times.) It’s immediately bettered by George’s “Wrack My Brain”, goofy enough for Ringo but grumpy enough for its auteur; it was also the first single, promoted by a video that continued his fascination with monster movies. Harry Nilsson could have used a boost himself at this time, but “Drumming Is My Madness” doesn’t do either of them any favors, and why is there a flute solo? “Attention” is another piano-based Paul knock-off that’s good enough for Ringo, but Nilsson’s “Stop And Take The Time To Smell The Roses” somehow manages to succeed, even as a co-write. (This too got a goofy video to match the nutty sound effects on the track itself.)

“Dead Giveaway” is a collaboration with Ron Wood that could use more balls, even with the presence of two of the Crusaders; still, this is one occasion where Ringo sings better than his co-writer. But who knew Woody could play sax? It wouldn’t be a Ringo album without at least one oldie, and “You Belong To Me” (aka “see the pyramids across [sic] the Nile”) is George’s other production here, taken at a “You’re Sixteen” pace. Carl Perkins’ “Sure To Fall (In Love With You)” was a favorite of Paul’s, who produced this pure country version with copious harmonies and prominent pedal steel. Stephen Stills showed up to contribute “You’ve Got A Nice Way”, which might have made helped improve one of his own albums, but it doesn’t work for this singer. And not only was there no need to remake “Back Off Boogaloo” disco-style, but Nilsson felt compelled to overdub a bunch of lines from other songs a la his version of “You Can’t Do That”. Even more confusing is that it begins with the riff from “It Don’t Come Easy”.

In addition to the promo clips, which got the occasional airing on the new MTV cable channel, Ringo got Paul to collaborate with him on a baffling short film called The Cooler, which not very many people saw or understood, even though it utilized Paul’s productions from the album. Despite all the push and Beatle involvement, the public at large did not take the time to Stop And Smell The Roses. While it was definitely an improvement over the last few, only diehard fans were sticking around, even for the half-hour it took to hear it.

But by the end of the decade, bootlegs had started appearing with outtakes from the sessions, somewhat stoking the legend of a lost Ringo album. The compilers of its first official CD release were kind enough to include detailed liner notes about the creation of the album, as well as the rejected songs among the bonus tracks. Honestly, they’re not that bad; “Wake Up” and the admittedly plodding “You Can’t Fight Lightning” are Ringo originals produced by Stills and McCartney respectively, while “Brandy” is a nice version of the O’Jays song produced with Ron Wood. Stills brought “Red And Black Blues” to the sessions, but it was never considered for any version of the album. A rough mix of “Stop And Take The Time To Smell The Roses” and two minutes of Ringo reading gun control PSAs don’t add much. But at least they spelled Laurence Juber’s name right.

Ringo Starr Stop And Smell The Roses (1981)—2½

1994 Right Stuff reissue: same as 1981, plus 6 extra tracks

Wednesday, February 18, 2009

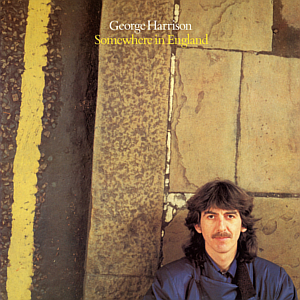

George Harrison 9: Somewhere In England

Just when George seemed to be enjoying himself, things went wrong. First, Warner Bros. rejected his original lineup for his new album, Somewhere In England, saying it wasn’t commercial enough. Then John died. He certainly had a right to be grumpy this time, and as a result, the mood permeates the tone of the finished product, obliterating the good vibes from the last album.

Just when George seemed to be enjoying himself, things went wrong. First, Warner Bros. rejected his original lineup for his new album, Somewhere In England, saying it wasn’t commercial enough. Then John died. He certainly had a right to be grumpy this time, and as a result, the mood permeates the tone of the finished product, obliterating the good vibes from the last album. “Blood From A Clone” puts the crux of the argument front and center, with backing that’s supposed to be contemporary. (Hey, they asked for it.) “Unconsciousness Rules” continues the dopey dance idea, with lyrics that skewer the genre. The melody for “Life Itself” brings the first enjoyable track here, but the words aren’t much more than a hymn in the tradition of “It Is He”. With different lyrics and easier meter it could have been a single. “All Those Years Ago” was the first musical statement by any Beatle after December 8th, and it’s pretty direct if a little forced. George pays tribute without suppressing any of his anger so it works. Paul, Linda, and Denny Laine supposedly sing backup, and Ringo’s on drums to keep it all in the family. “Baltimore Oriole” is the first of two old Hoagy Carmichael tunes here; by putting his own stamp on it, it’s surprisingly one of the most enjoyable songs on the album.

“Teardrops” starts off the second side, sounding exactly like Elton John’s early ‘80s stuff. This wasn’t on the first version of the album, leading us to think it was new. The dour words don’t match the tune at all. It seems a little odd to have something this radio-friendly coming from George, especially at this point. “That Which I Have Lost” annoyingly mixes a cowboy melody with a music hall swing, while the words seem to refer to Bob Dylan’s recent Christian conversion. “Writing’s On The Wall” is laid-back and pleasant, yet repetitive and forgettable. Originally the opening track on the original sequence, “Hong Kong Blues” is the lesser Hoagy Carmichael song here, complete with dated racial references. It all finally ends with “Save The World”, where George takes his sermonizing to tell his heathen fans to be nicer to the environment. There are nice passages here that don’t coalesce, along with some hilarious sound effects, and you can just barely hear a track from Wonderwall Music on the fade.

If Warners didn’t like the first version, it’s safe to say they only approved this one to cash in on the post-murder hype. The replaced songs would all officially, if briefly, surface on CDs packaged with expensive leather-bound limited editions of his lyrics, as well as on some B-sides, but sadly, not on the album’s posthumous reissue. (Instead there is an acoustic demo of “Save The World” that shows its intricacy without sparing the message.) But after the quality of the previous album, we were back to wondering why he bothered making records if he couldn’t enjoy the process.

Footnote: in at least one interview before his death, John complained about how George remembered every “two-bit guitar player he’d ever met” in his autobiography I Me Mine, but didn’t spend more than two words on him. George did make sure to include a dedication on the inner sleeve of Somewhere In England, even going so far as to use John’s preferred initials. So there.

George Harrison Somewhere In England (1981)—2

2004 Dark Horse Years reissue: same as 1981, plus 1 extra track