Nick Drake took elements of a variety of influences, from Dylan folk to English guitar, jazz to classical, yet emerged with something somewhat indescribable, something that has to be heard to be appreciated. Five Leaves Left, his debut album, is a showcase for his soft voice and inspired guitar—in several non-standard tunings—and an excellent place for the curious to start.

The opening song, “Time Has Told Me”, is a perfect introduction to Nick Drake. So many of the elements of what he’s about are contained in these four minutes, from the intricate picking to his trademark third-beat phrasing. It’s a deceptively hopeful song, with underpinnings of forbidding amidst the declaration that the narrator has found his soulmate. Equally mysterious is “River Man”, which lopes along in and out of C and C minor in 5/4. We hear strings for the first time, and the effect is very river-like, with sweeping and urgent yet subtle movements. (The arranger was only used on this track; all other arrangements would be pointedly different. Nick could not be accused of repeating himself.) “Three Hours” is almost Indian in flavor, with its droning undercurrent, alternate-tempo midsection and conga from a guy who’d one day play with the Stones. The lyrics are even more impenetrable that the ones that have come before; apparently they make perfect sense if you’ve traveled three hours from London at sundown, which we haven’t. Already three songs in, we’ve heard music that is incredibly unique and different. The dramatic, somber string accompaniment of “Way To Blue” nonetheless provides something of a lift. There is no guitar here; just Nick singing to Robert Kirby’s masterful baroque arrangement. One of his rare songs performed in standard tuning, “Day Is Done” teems with the despair and edgy regret that comes with an unfulfilled day. By this time he has left an impression as something of a mysterious sad sack, the kind girls mooned after on campuses. The strings come to a halt with a slight ritard, closing side one.

“Cello Song” starts side two, and builds a string at a time until suddenly shifting into a new theme on which the rest of the song lies. It’s similar to “Time Has Told Me” in its reassuring hopefulness to the owner of the pale, frail, strange face who he sees as far away from him, but able to lift him to a “place in the cloud”. “The Thoughts Of Mary Jane” is very much in the fey Donovan mode, with a shrill flute in the mix. It’s reminisicent of some of the songs on the first Mary Hopkin album with their delicate, fragile China cup quality. (The Mary Jane here could be a woman, or what he was smoking; biographers lean towards the latter.) Despite its jaunty, almost vaudeville accompaniment, “Man In A Shed” is a fable as old as the hills. It may be his most blatant statement of pining, but it’s hardly the saddest, as you can hear the wink in his delivery. The music on the coda nicely echoes the relaxed opening, with a variation that’s very effective. “Fruit Tree” also starts with a slowly building figure that turns into something else entirely. This rumination on fame, notoriety and lasting memory is rather profound for a 20-year-old that hadn’t become close to a star at this point. Still, we can’t but think he harbored some desire for that hollow, fleeting recognition. With its piano suggesting last call, “Saturday Sun” finishes the album. He lived much of his life in a climate where it rains everyday, sometimes several times on the hour. The sun is a virtual wake-up call, with people rubbing their eyes, realizing what’s changed, what’s gone, what’s really happening. This track is the most like Astral Weeks—one contemporary album to which this album is compared—with its use of vibes and brushed drums. The silly couplet at the end (and again, you can hear him smiling through his vocal) glides though the jazzy rhythm section, and the album floats away.

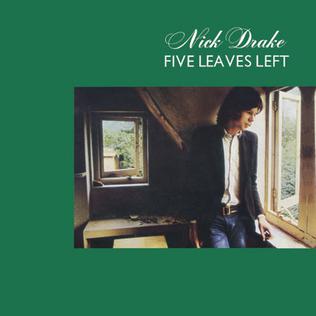

Five Leaves Left is subtle, yet shows a lot of breadth and depth in its simplicity. That’s not to say it’s simple; it just is what it is and nothing is wasted. It is a nearly perfect album. His music can be considered timeless, yet it was very much a product of its time. Even the cover photos work—the woodsy suggestion on the front, and the passive observer on the back. In both cases, his face is bemused.

Save for two similar but different posthumous compilations, his estate resisted any kind of dig through the vaults to celebrate the album, even past its 50th anniversary in a time when seemingly every album that age got a deluxe treatment. So it was very surprising when The Making Of Five Leaves Left was released in 2025. This wasn’t a forensic trawl through the sessions, but a carefully curated (and packaged) selection of recently unearthed studio sessions and demo recordings, culminating in the most recent remaster of the album itself. All the extras could have been contained on two CDs instead of three, but record companies like to have them match the vinyl sequence as closely as possible and jack up the price at the same time. They’re also not sequenced chronologically, making for a disjointed listen at times.

The alternate takes are illuminating, if only because he sounds engaged, focused, and in good spirits throughout. We get to hear some tracks with discarded arrangements, and even some parts that were adjusted along the way, mostly showing that his instincts served him well when something clearly wasn’t what he wanted. There’s a wonderful moment before a take of “River Man” where he’s experimenting with a possible intro, and finds a chord sequence that would one day turn up in “Things Behind The Sun”. A tape recorded whilst still at university to help Robert Kirby write arrangements includes the first official release of “Mickey’s Tune”, a jazzy number similar to but bettered by “Joey”, as well as a brief dramatic, cascading yet untitled instrumental that might have worked to set up “Made To Love Magic”. (The previously released alternate take of that and “Clothes Of Sand” are glaring in their absence.) These are the only buried treasures, if any. The compilers could easily have included vocal-and-guitar-only mixes, or some with just the strings backing, but for the most part they try to keep it organic.

Nick Drake Five Leaves Left (1969)—4½

2025 The Making Of Five Leaves Left: same as 1969, plus 32 extra tracks

No comments:

Post a Comment