Neil gets the first shot in with “Mr. Soul”, a paranoid trip through the clubs on Sunset Blvd., with a wonderful riff turning “Satisfaction” upside down and dueling solos. “A Child’s Claim To Fame” is a strong writing debut from Richie, even more so because the lyrics refer to his irritation over Neil’s wavering dedication to the band. (That would be James Burton on the dobro.) Stephen revives the buzz that opened “Baby Don’t Scold Me” and extends it into a feedback drone base for the jazzy “Everydays”, followed by “Expecting To Fly”, Neil’s first really pretty, really sad song, all lush orchestration from Jack Nietzsche. But it’s “Bluebird” that hints at the power of the band as a unit, all those drop-D guitars intertwining, though this studio version detours into a banjo-led coda.

“Hung Upside Down” keeps it going on side two, the verses sung by Richie and Stephen answering with the choruses. This album’s hidden gem is “Sad Memory”, a heartbreaker from Richie, unfortunately derailed by Dewey Martin’s misplaced Stax soul workout “Good Time Boy”. Things get back on track for “Rock & Roll Woman”, which sports an “inspiration” credit to David Crosby, in a wonderful case of foreshadowing. For the finale, what sounds like a live recording of “Mr. Soul” with Dewey soul-scatting the vocal shifts into the first of several multi-structured verses of Neil’s experimental “Broken Arrow”. The poetic verses are separated by such sound effects as a ballgame organ, military drums, a jazz combo, and a disappearing heartbeat. Heavy stuff.

Even with the band members mostly working separately under the guise of unity, much like the Monkees and even the Beatles would become, Buffalo Springfield Again deserves to be called seminal. It’s a solid step forward, showing great potential for all concerned.

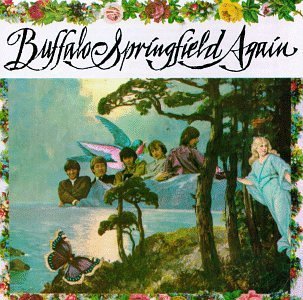

Buffalo Springfield Buffalo Springfield Again (1967)—4

No comments:

Post a Comment