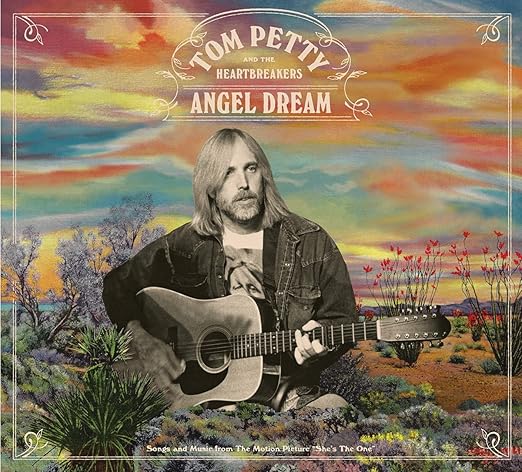

Tom Petty’s first album for his new label was a solo album, but in name only;

Wildflowers features Mike Campbell on every track and Benmont Tench on most of them, with future Heartbreaker Steve Ferrone behind the kit in one hell of an audition. (Howie Epstein shows up here and there too. And so does Ringo!) Working with Rick Rubin suited Petty well, with more natural production that fit his simple style better than the boomy Jeff Lynne sound. Even using only three or four chords, he came up with some great new songs.

When we say great, we’re not kidding: “You Wreck Me” is a fun rocker; “It’s Good To Be King” does Mel Brooks proud; “Honey Bee” rides a basic riff down the white line; “Don’t Fade On Me” is a satisfying trip to the swamp. And if he’d only ever written the gorgeous “Wake Up Time” and nothing else in his long career, he could still be proud.

On top of that, there are ten other tracks to keep you busy. The title track has become a sentimental favorite over the years. “You Don’t Know How It Feels” follows a robotic drumbeat through harmonica breaks and a notorious reference to a joint that is still censored on corporate radio. “Time To Move On” and “Only A Broken Heart” are simple and perfect. “Cabin Down Below” and the horn-flavored “House In The Woods” (which hearkens back to George Harrison’s “Long, Long, Long” via Dylan’s “Sad-Eyed Lady Of The Lowlands”) make for excellent variety, while “Crawling Back To You” sounds something of a sequel to Springsteen’s “Spirit In The Night”. “Hard On Me” and “A Higher Place” sound like other songs we’ve heard before, but we haven’t placed them yet; hence their success.

While it has more of a produced studio vibe than Full Moon Fever—which was largely concocted in a garage—Wildflowers has a warm, comfortable feel throughout that’s not at all dated, unlike his first so-called solo album. Of course, he toured behind the album with the Heartbreakers. After all, who else could do these songs justice?

Even before his death, the album emerged as a critical and fan favorite, high above the rest of his catalog. In the last decade of his life he occasionally spoke of expanding the album to include songs he would’ve had he been allowed to put out a double. After years of teasing, Wildflowers & All The Rest finally emerged at the end of 2020, in several frustrating permutations.

The basic set added a disc of ten candidates for the double, four of which would end up in different mixes or takes on She’s The One. Some of these had never been heard before, like “Something Could Happen”, which features Stan Lynch on drums; unfortunately every reference to him in the liner notes is backhanded. “Leave Virginia Alone” and “Harry Green” suggest he was considering an album of characters a la Southern Accents; frankly, the dark confession of “Confusion Wheel” is more fitting. “Climb That Hill Blues” is a stark acoustic alternate to the familiar arrangement, while “Somewhere Under Heaven” is an early experiment with Mike Campbell before Rick Rubin came on board.

Two of those extras appear as demos, but these aren’t grainy cassette-quality boom box jobs. By this time Tom and Mike both had home studios with decent equipment, so these are all perfectly releaseable. To further the point, the Deluxe Edition added a disc of further solo home demos. Outside of the occasional shuffled verse or bridge, it’s amazing to hear how much of these songs were basically formed before he brought them to other players. (In fact, the original instrumental bridge for “Wildflowers” itself would form the basis for “To Find A Friend”.) A few songs never seemingly made it to the album sessions, such as the lovely “There Goes Angela (Dream Away)”, and “A Feeling Of Peace”, which already sounds very Heartbreakers-like. A tune now named “There’s A Break In The Rain” sports the chorus of what would be “Have Love Will Travel” a decade later.

A fourth disc presented a sprawling assortment of live versions, including songs not the original album, mostly recorded in the 21st century. It’s something of a companion to The Live Anthology, mixed and sequenced seamlessly, where you can only guess the age of the recording from the state of Tom’s voice. We’d’ve preferred the version of “Honey Bee” from Saturday Night Live with Dave Grohl on drums, but “Walls”, “Drivin’ Down To Georgia” (which was recorded after its appearance on that live set), an 11-minute exploration of “It’s Good To Be King”, and even a run through “Girl On LSD” help keep it interesting instead of just the album played faster.

A pricey and limited Super Deluxe Edition, available only via the official website, added another CD worth of leftovers from the sessions, mostly alternate takes, some including Stan on drums. (Kenny Aronoff plays on two tracks, while Ringo helms a version of the title track.) If only for the definitive studio take of “Girl On LSD”, as well as the acoustic B-sides “Only A Broken Heart” and “Cabin Down Below”, some of us would have preferred this disc in the Deluxe Edition over the live disc, even with the repeats from An American Treasure, but but again, nobody ever consults us on these things. Even the galloping “You Saw Me Comin’”, which previews “Don’t Fade On Me” via the similar outtakes on the Playback box, is worth more exposure. An early “House In The Woods” with Stan has a Dead-inspired mid-section that was thankfully jettisoned for the album, but it’s still cool to hear. (As if they listened to us, Finding Wildflowers (Alternate Versions) was a welcome standalone release the following spring. We’re guessing it offset all the unsold Wildflowers-themed candles, Xmas ornaments and whatnot on the online store shelves.)

The culmination of several years of work, Wildflowers & All The Rest is an excellent testament to both the man and the album. Should the estate tackle any other record to dig into, the bar has been set.

Tom Petty Wildflowers (1994)—4

2020 Wildflowers & All The Rest: same as 1994, plus 10 extra tracks (Deluxe Edition adds another 29; Super Deluxe another 15)

Tom Petty Finding Wildflowers (Alternate Versions) (2021)—3½

Unless you were really, really hip in the late ‘70s, chances are you hadn’t heard of The Soft Boys until much later, in the context of being Robyn Hitchcock’s first band, or maybe as the precursor to Katrina & The Waves. At any rate, as their catalog has been reissued for the third time, a summary is overdue.

Unless you were really, really hip in the late ‘70s, chances are you hadn’t heard of The Soft Boys until much later, in the context of being Robyn Hitchcock’s first band, or maybe as the precursor to Katrina & The Waves. At any rate, as their catalog has been reissued for the third time, a summary is overdue.

.jpg)