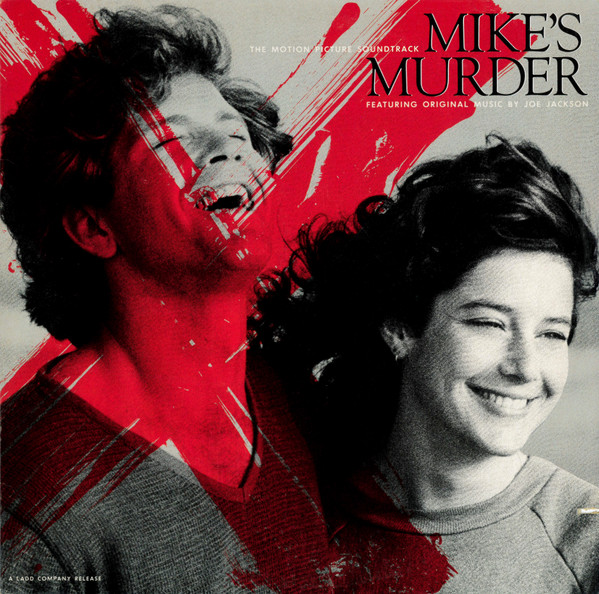

Smart producers put the hit at the top of side one, and “Brown Eyed Girl” is followed by the slightly brooding “He Ain’t Give You None”. That runs for five minutes, a little over half the length of what follows. “T.B. Sheets” is a two-chord slog under a narration by a guy who’s uncomfortable watching his girlfriend die of tuberculosis, to the point that his harmonica seems to be in the wrong key.

The wince-inducing arrangement of “Spanish Rose” isn’t helped by his phrasing, though we do hear something of a preview of “Ballerina” here and there. “Goodbye Baby (Baby Goodbye)” sounds a little different, probably because Berns foisted it on him for the “Brown Eyed Girl” B-side (and subsequent royalties, an old producer’s trick). “Ro Ro Rosey” succeeds despite its simplicity, but simple is not what we’d call “Who Drove The Red Sports Car”. Its tension is smacked aside by a generic “Midnight Special”, with the girls mixed way too high.

Van didn’t want this album out to begin with, since (he says) he considered them singles and potential B-sides. He also hated the cover, which is hideous. Most of the reason why we’re addressing it now is because everything he recorded in this brief period kept popping up like the proverbial bad pennies.

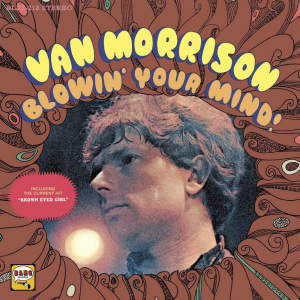

After Bert Berns died, his widow continued to run the label for years, and since she never liked Van anyway, likely didn’t prevent various cash-in compilations from coming out once he’d gone into the mystic as the Belfast cowboy. Misleadingly titled, The Best Of Van Morrison was released in the wake of Moondance, and boldly featured a photo from the back cover of Astral Weeks. Granted, the album did include “Brown Eyed Girl” and four other songs from Blowin’ Your Mind, but the other five songs came from later 1967 sessions. “It’s All Right” drags, while “Send Your Mind” is much more furious. “The Smile You Smile” and “The Back Room” are good examples of his lyrics starting to become more impressionistic. “Joe Harper Saturday Morning” is the best blend of lyrics and melody, but throughout these tracks, the guitarist is way too up front.

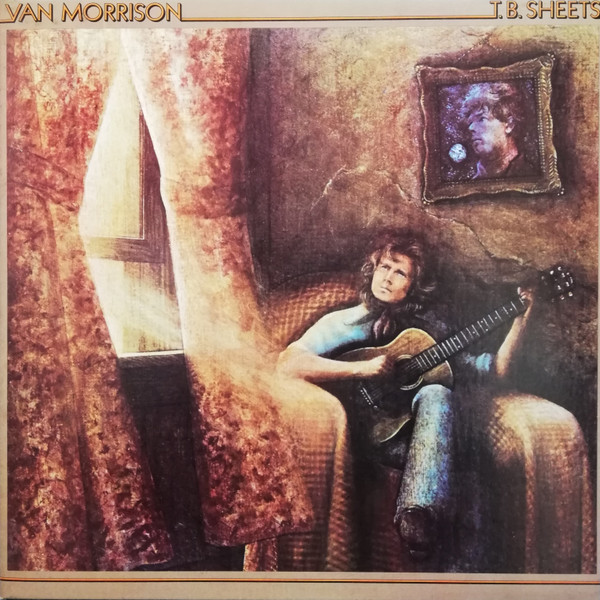

Three years later, T.B. Sheets sported a cover painting showing the artist in full creative reverie. Five songs were again repeated from Blowin’ Your Mind, three of which had also been on Best Of, plus “It’s All Right” and the now-title track. The draw to even the unsure were two earlier, previously unreleased takes of Astral Weeks songs. Along with a few extra lyrics, “Beside You” sports a spellbinding guitar part that strains to maintain its pace throughout, but “Madame George” takes the idea of a party too literally, removing all of the mystery and, frankly, the beauty of the eventual masterpiece. At least the gatefold offered some photos dating from the time of the recordings—unlike the cover art—as well as full lyrics laid out like English poetry.

By the ‘90s, Sony had obtained the rights to the Bang label, and in the wake of his late ‘80s resurgence, Bang Masters collected all of the songs from the three albums into one set, though “He Ain’t Give You None” was an alternate take, remixed for modern dynamics. Added bonuses were another take of “Brown Eyed Girl”, the “La Bamba” rip-off B-side “Chick-A-Boom”, and a charming demo of “The Smile You Smile”. (Around this time Blowin’ Your Mind and T.B. Sheets were also reissued on CD, the former with bonus tracks in the form of alternate takes of the songs from side two.)

Adding to the nuttiness of the legacy, several compilations of dubious legality began appearing around this time with a disc’s worth of truly odd songs, known as the “contractual obligation session”. Having been informed in late 1967 that he still owed Bang more material, he recorded 31 songs in 35 minutes, written on the spot using most of the same chord changes and played on an out-of-tune acoustic. He started with various riffs on “Twist And Shout”, then moved to similar exhortations and copies of “Hey Joe”, “Hang On Sloopy”, “La Bamba”, and the like. A figure named Dumb George, never once called Madame, appears several times. He sing-speaks about waiting for “The Big Royalty Check”, undermines the message of “T.B. Sheets” with “Ring Worm”, and ridicules his former mentor via impressions as well as such titles as “Blowin’ Your Nose” and “Nose In Your Blow”. If you’re looking for grains that will sprout into future epics, you’ll be gravely disappointed. He acknowledges this halfway through with the self-explanatory “Freaky If You Got This Far”.

Fifty years after that first standard contract, he signed what must have been a pretty sweet deal with Sony to pick up his catalog, as The Authorized Bang Collection gathered (just about) everything from the Bang sessions in one packed set. (Not only did Van approve of the compilation, he even provided liner notes.) The first disc has the original Bert Berns stereo mixes of Blowin’ Your Mind, followed by the five songs that debuted on the 1970 Best Of, the two Astral Weeks alternates from T.B. Sheets in mono, “Chick-A-Boom” in mono, and the “Smile You Smile” demo. The second disc consists mostly of alternate takes, some with session banter, beginning with single versions of “Brown Eyed Girl” (“laughin’ and a-runnin’, hey hey” in place of “makin’ love in the green grass”) and “Ro Ro Rosey”. Alternates of “Beside You” and “T.B. Sheets” are worthy of comparison, and 15 minutes of successive attempts at “Brown Eyed Girl” provide a rare look at the making of a hit single. Finally, the third disc has all the contractual obligation songs in case you really want to hear “Want A Danish” in best-ever sound.

Van purists should definitely spring for the Authorized set; those merely curious should be fine with Bang Masters. Keep in mind that he would abandon this sound as soon as he could. Otherwise, “Brown Eyed Girl” is easy enough to find on other collections.

Van Morrison Blowin’ Your Mind (1967)—2½

1995 Sony MasterSound Edition: same as 1967, plus 5 extra tracks

Van Morrison The Best Of Van Morrison (1970)—2

Van Morrison T.B. Sheets (1973)—2½

Van Morrison Bang Masters (1991)—3

Van Morrison The Authorized Bang Collection (2017)—3

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-1167071-1420574262-6604.jpeg.jpg)