In addition to his increasingly experimental contributions to Monkees albums, Michael Nesmith also displayed a defiant affection for country music. As the band dwindled out of commercial favor, he began stockpiling songs, which usually began as poetry pieces with arbitrary titles, that he hoped to one day issue on his own.

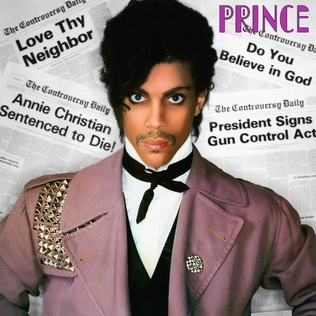

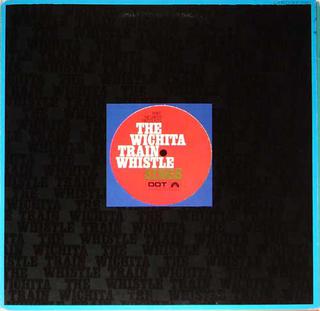

His first major extracurricular experiment reared its wacky head in the summer of 1968.

The Wichita Train Whistle Sings was recorded over two days with dozens of L.A.’s finest session players, and presented ten instrumental arrangements of Nesmith tunes, some already familiar from earlier Monkees albums. The record is best appreciated if one is fluent with the more standard recordings, because the styles used here range wildly from easy listening to high school marching band, with prominent banjos and a determination to be just plain nutty. Laughter at zany guitar lines is left in, along with the notorious sound of

Tommy Tedesco’s prized Telecaster being hurled into the air and crashing to the floor.

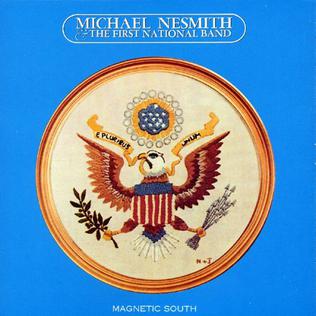

Once free from the Monkees, he strove to fully explore the possibilities of blending the professional Nashville sound with his own idiosyncratic tendencies. Such a blend was already evident on “Listen To The Band” and “Good Clean Fun”, both chosen as Monkees singles, and after settling on some friends as his rhythm section, he was able to rope in pedal steel player Red Rhodes to complete the First National Band. In less than a year’s time, they recorded three albums’ worth of material, released faster than they could be recorded. Just like other early practitioners of what would become country rock would take decades to get any kind of respect, they were pretty much ignored at the time, being too country for rock and not country enough for country.

Magnetic South came first, frontloaded with Nesmith originals, some of which were those Monkees leftovers: the samba-flavored “Calico Girlfriend”; the all-too-brief “Nine Times Blue”, which goes into the nearly funky “Little Red Rider”; “The Crippled Lion”, a hidden Nesmith gem; and the surprising hit story-song “Joanne”, which cuts right to “First National Rag”, something of a commercial break telling the listener to flip the record over. There he pulls out the yodel for “Mama Nantucket” and “Keys To The Car”, and gets a little ambitious with “Hollywood”, but by ending with two covers—the straight croon of “One Rose” and a “mind movie” rendition of “Beyond The Blue Horizon”—it’s a nice little trip.

Loose Salute was half in the can by the time

Magnetic South came out, and is even more country, but with only one cover (“I Fall To Pieces”). “Silver Moon” with its mild island lilt was a mild hit single, and probably the high point. Monkees fans today have already heard several better takes of “Conversations” (a.k.a. “Carlisle Wheeling”), and the original single of “Listen To The Band” was so definitive, even by his own admission, why do another? “Tengo Amore” is enticing until the vocal kicks in, a frighteningly accurate amalgam of Stephen Stills’ worst Latin tendencies. Where the first album was refreshing, this one’s almost ordinary.

By the time

Loose Salute was on the shelves, the rhythm section had already left, so

Nevada Fighter was finished with session pros. This time the sides were split, with Nesmith originals on side one and covers on side two. The originals are of fine quality, particularly “Propinquity (I’ve Just Begun To Care)” (another Monkees refugee), “Only Bound”, and the rocking title track. With the exception of “Tumbling Tumbleweeds”, the covers come from the pens of previous Monkee collaborators Harry Nilsson, Michael Murphey and Bill Martin, with a surprising choice in “I Looked Away”, best known as the opener for Derek and the Dominos’

Layla. Red Rhodes’ solo “Rene” closes the album, and the chapter, fittingly.

The three First National Band albums have been in and out of print over the years, and further reissues have gone as far as abridging them to cram the most music in. If one enjoys Nesmith’s voice and writing, and can handle a lot of pedal steel guitar, they’re worth checking out, particularly for fans of Gram Parsons. If anything, they run rings around Changes.

Michael Nesmith The Wichita Train Whistle Sings (1968)—2

Michael Nesmith & The First National Band Magnetic South (1970)—3

Michael Nesmith & The First National Band Loose Salute (1970)—2½

Michael Nesmith & The First National Band Nevada Fighter (1971)—3

.jpeg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-4323373-1423122477-9861.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-1840949-1416516014-9015.jpeg.jpg)